EMBA JB Braly

Most managers are trained to approach decisions as yes or no questions. We compare the choices based on known details, pros and cons, and say yes or no. Even our governance is structured for this type of decision-making. We present a compelling enough case to choose A or B. At MIT, I learned that there are better ways to make decisions. The critical difference is the impact of external factors and the timing of decisions.

As I was preparing a business case at work – which I had done many times before – I applied my learnings from class. The general question was whether to spend money to shut down an existing facility and build a new one, or to continue operating the current building with limited capacity. Applying concepts from classes, I realized that this decision wasn’t as simple as I had thought in the past.

Create a more complex decision tree

I started out evaluating the usual factors in a decision tree: pros, cons, costs and risks. However, as I learned in class, I added timing and external factors. I asked, “What external factors may impact the success of this decision? What events will happen in the future that will provide more data for this decision?”

In my case, the decision to shut down the facility and build a new one was contingent upon the development of a new technology and a future acquisition. If we succeeded at developing new technology, we wouldn’t need a new building. And if we were acquired, what if the new leaders took a different position on future strategy? My “aha moment” was when I realized that the key question wasn’t whether to build or not, but instead, how long we could wait to make this decision before we impacted our product supply.

I needed to determine when we needed to complete construction before product supply would run out. I worked with Engineering to figure out the timeline for when we needed to break ground and get funding approved. I worked with R&D to figure out when we would need more capacity based on anticipated patient demand and current product supply. Based on that analysis, I knew exactly how long we could wait to make the decision. We could wait up to one year. By waiting, we would have more information on the new technology and a better sense of the need for a new facility.

Articulate external factors in the story

The recommendation to wait wasn’t without risk or cost. The company had to spend money to stay in the current facility. Delaying the decision to build would cost more money upfront. So, I had to articulate the cost of avoidance. If we spend this much money now, we may save another amount later.

But it wasn’t enough to just do the analysis and hand it over. I had to convey these external factors in a story to convince other stakeholders that delaying the decision was the right call. I had to go beyond the basic yes or no decision they were expecting and address the elephant in the room: the external factors. I focused the story on the positives of being financially responsible and likelihood of saving money in the long run.

Consider political and cultural factors

I also considered political and cultural elements in my recommendation. How would everyone in the room be affected by the decision to delay? It was important for everyone to feel OK with delaying the decision. Nobody else in the room was taking this class with me, so I had to consider that they had different expectations about the decision. Instead of the traditional power point with pros, cons, costs, and risks, I presented scenarios of how our decision could be influenced at different points in time. I presented a very watered-down decision tree to show the possible impacts of external events. Even if we later decided to build a new facility, I showed how it was better to wait to make the decision.

The takeaway: Sometimes the decision is when to decide, rather than what to decide.

Ultimately, everyone accepted my recommendation to wait until we learned about the acquisition and had more data to assess the situation. It turned out to be a smart move because the location of the new facility changed. Had we decided to move forward with building a new facility six months ago, we would have wasted a lot of money by building in the wrong country.

The big takeaway is that we must discover when we will have what information, and how that could influence our decision at each time period. This new perspective helped me adjust my work to ensure that the organization is armed with the ability to make the right decisions at the right time.

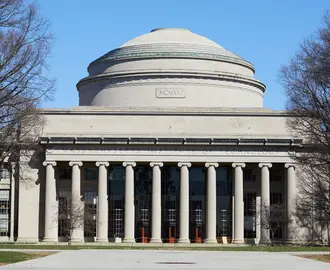

Jen “JB” Braly, EMBA '19, is Vice President of the Program Office at Moderna in Cambridge, MA and a veteran U.S. Air Force officer.