Sustainability

Why impact investors are embracing systems change

It’s no longer enough to invest solely in single-point solutions. Here are nine ways impact investors succeed in driving systems-level change.

Just a few decades ago, impact investing existed mainly on the fringes. Now it's a global market estimated at $30.3 trillion, and it isn’t unusual for investors to want to buy shares of companies that are making progress on environment, social, or governance issues.

It’s a start, but investors who want to generate lasting change need to do more than invest in single companies, said Alban Yau, a graduate research assistant in the MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative.

Currently, impact investing focuses primarily on supporting technologies or companies individually, which creates an isolated impact. “But the challenges we face today are complex and systemic, with interconnected social and technical factors,” Yau said.

What’s needed is systemic investing — a new approach that embraces systems transformation, deploys capital with a broader intent, and replaces a project-by-project mentality with new methodologies, structures, capabilities, and decision-making frameworks.

And that can prove challenging, Yau said. “Systems change remains an abstract concept for many impact investors.”

“This is really the new frontier in impact investing — taking a systems view and coordinating investment across asset classes, including philanthropy, in ways that can enhance both value and impact,” said director of the Sustainability Initiative.

In writing his master’s thesis, “How Can Impact Investors Enable Systems Change?” Yau analyzed case studies from TWIST: Investing for Systems Change, a global community of investors, practitioners, and facilitators who are actively deploying capital and/or facilitating processes for systems change. He also consulted numerous case studies and research on socio-technical transitions and social systems change.

Yau arrived at nine key levers that investors can pull in combination to best create systemic change:

1. Solution experimentation

Innovation comes with uncertainty, “and the emerging field of catalytic capital has been critical in trying to fill that gap,” Yau writes.

Investors often contribute funding to immature technological or social innovations to address environmental issues through experimentation, as was the case with electric vehicles in the early 2000s and is happening today with companies that keep produce from going to waste, Yau said.

Catalytic capital, whereby investors take on more risk or accept lower financial expectations in order to jumpstart projects and attract third-party investment that would otherwise not be possible, is one of the fastest-growing subsets of impact investing.

2. Solution scaling

Yau said that in addition to funding innovation, investors should continue to use their funds to help scale proven solutions. Those could be technologies like solar, wind, and electric vehicles — “anything that has been proved in the market and requires capital to increase its magnitude,” whether through funding or technical assistance, Yau said.

Research conducted by the nonprofit Prime Coalition identified four areas where gaps in financing can hobble entrepreneurs — and where investors can help.

Climate innovators can run into trouble if they are:

- Trying to finance early development costs, such as buying real estate, engaging in pre-engineering design, or securing permits.

- At the late-demonstration stage, which can require significant project development and construction costs.

- Building first-of-a-kind commercial projects that demonstrate commercial feasibility but may require more iterations to prove economic feasibility.

- Working on small, distributed projects, such as rooftop solar or ground-source heating solutions, that won’t generate returns high enough to attract venture funding.

3. Orchestration and network

Another way to drive impact is by initiating coalition-building within a designated network.

For instance, Regen Melbourne is an alliance of more than 180 organizations supported by different funders who are “deeply connected to Melbourne and want to invest in the collaboration they would like to see, not just single projects working in silos,” Yau writes in his research paper.

The alliance was created as a way to drive positive change following Australia’s devastating 2019–20 Black Summer fires and the COVID-19 pandemic. The alliance conducted workshops, leadership interviews, roundtables, and data analysis and then released the report “Towards a Regenerative Melbourne,” which provides a road map for combating climate change, ocean acidification, chemical pollution, and more.

4. Data and knowledge

Investors can also partner with research institutions to develop publicly available open-source resources that other stakeholders can use to take action.

For example, a group of investors behind ReFED (which uses technological and social innovations to fight food waste) helped support the launch of the Insights Engine, an open-source interactive online data center that has empowered more than 60,000 users, including large food companies, state governments, and startups, to delve into nuanced solutions tailored to specific challenges.

The platform was developed by consolidating and analyzing public and proprietary datasets and was supplemented with information from academic studies, industry papers, case studies, and industry expert interviews.

5. Human capital

Another idea: Consider supporting human talent by funding programs that help students, policymakers, or those working at nonprofits develop the necessary mindset and skills for the future. This could include investing in educational organizations that train technicians needed to transition to a new technology — solar panel installers, for instance — or sponsoring courses to develop new leadership in existing businesses. Investors may even build a new academy or school.

6. Physical infrastructure

Sound infrastructure goes a long way toward improving the likelihood that businesses and investors will back a project because it reduces operational risks and enhances market accessibility.

Unfortunately, infrastructure investments are often made through project finance and debt-based mechanisms, which tend to shy away from risk, especially when it involves cutting-edge technologies. “Investors can play a crucial role in overcoming these challenges,” Yau writes.

For example, in Switzerland, one of the key strategies of the TransCap Initiative’s Net-Zero Mobility Prototype is to support the buildup of photovoltaic systems and charging infrastructure for electric vehicles, especially in underserved areas where the utilization rate is lower, to attract further operation and funding.

7. Established company behavior

Large, established companies play a big role in systems change because of their significant scale, Yao said. From their supply chains to their customers, large corporations send powerful signals to the market through their actions.

For example, to fight food waste, ReFED advised Kroger on launching an innovation fund that ended up becoming a valuable avenue for waste prevention technology startups to test their solutions in large corporate pilots.

Shareholder engagement is another idea. When seeking to improve access to reproductive health services for American women, the Tara Health Foundation invited other investors to join a shareholder coalition. With over $500 billion in assets under management, this coalition has filed investor letters in 30 public companies to influence their internal health policies.

8. Social norms and public awareness

Investors can also invest in campaigns to change social norms because “a shift in norms and awareness can create a movement in consumers and businesses, mobilize more resources, and generate the political will to trigger institutional change,” Yau writes. “Investors have been found investing in multichannel campaigns, such as events, press and publications, movies, and documentaries, to change the norm.”

For example, the Break Free From Plastic initiative was started to dispel the notion that plastic pollution was caused by individuals failing to take responsibility for their waste. Investors funded a “brand audit” campaign whereby people collected plastic waste on beaches and counted consumer labels to show that the top plastic polluters are companies, not individuals.

9. Policy and regulation

Policy and regulation can most effectively drive systems change, Yau said, but those are among the most difficult for investors to influence.

“Policymaking and government decision-making vary significantly worldwide, while in most democratic countries, this lever changes very slowly and is full of conflict of interest,” Yau writes.

To succeed, investors often partner with campaigns to advocate for regulation. One example is Fair By Design, which pairs a venture fund (the Fair By Design Fund, managed by Ascension Ventures) with an advocacy campaign run by the Barrow Cadbury Trust on behalf of a group of foundations that aims to create policies to help the poor. The fund provides capital to do-good companies such as Kettel, which helps people build credit and save for a down payment to buy a home.

You can’t do everything everywhere all at once

When it comes to choosing which levers to use, Yau said you can’t do everything everywhere all at once. “Don’t spread yourself too thin.”

Depending on the situation, “you might end up pulling every lever, but not at the same time,” he said. “You might pull something first, and then, when conditions shift, you might start to pull the other levers.”

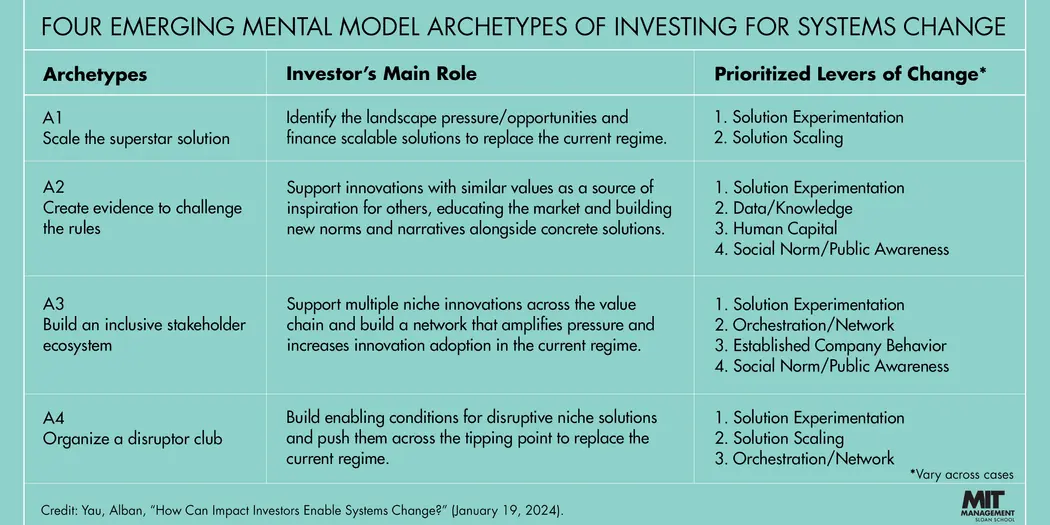

While there’s no general step-by-step guidance, Yau observed four emerging mental model archetypes that prioritize different combinations of levers:

- Scale the superstar solution.

- Create evidence to challenge the rules.

- Build an inclusive stakeholder ecosystem.

- Organize a disruptor club.

Of the nine strategies, Yau said the most popular among systemic investors are solution experimentation and network orchestration.

The former is a longtime favorite of impact investors; the latter is less common but gaining traction, Yau said.

Investors are recognizing that they can’t change an entrenched socio-technical system on their own — they have to collaborate with other stakeholders.

“Their investments have to be nested with broader intervention by other stakeholders to overcome the inertia and make a shift,” Yau said. “We find that impact investors have great potential to make a big difference in complex challenges, especially when they don’t just invest in single-point solutions seeking isolated impact.”

Read also: Systemic Investing for Social Change