Innovation

Will regulating big tech stifle innovation?

Seventeen years after the landmark Microsoft antitrust case, big tech firms have more market power than ever. We may need new ways of preventing monopoly without slowing innovation.

The titans of big technology have grown to dwarf the rest of the U.S. economy in recent years, and their influence is being felt in nearly every corner of our daily lives. Poke a smartphone screen, and that new gadget you’ve had your eye on appears on your doorstep as you collaborate with colleagues in the cloud.The market power of most of those companies continues to grow at a rapid clip, with Apple passing $1 trillion in market value earlier this year—the world’s first company to clear that bar. Amazon followed in early September.

With such scale and influence, to what extent, if at all, have these companies become monopolies, and should they be more closely regulated? Could stricter regulation have unintended effects on the pace of innovation? The answer is more complex than it was for past industries that became the target of antitrust action, like telecommunications, oil, and railroads, experts say, but the companies have certainly been raising some eyebrows in recent months.MIT Sloan economist John Van Reenen said the potential for regulating big tech is being taken more seriously now than it was two decades ago because the economy itself has fundamentally changed in that time.

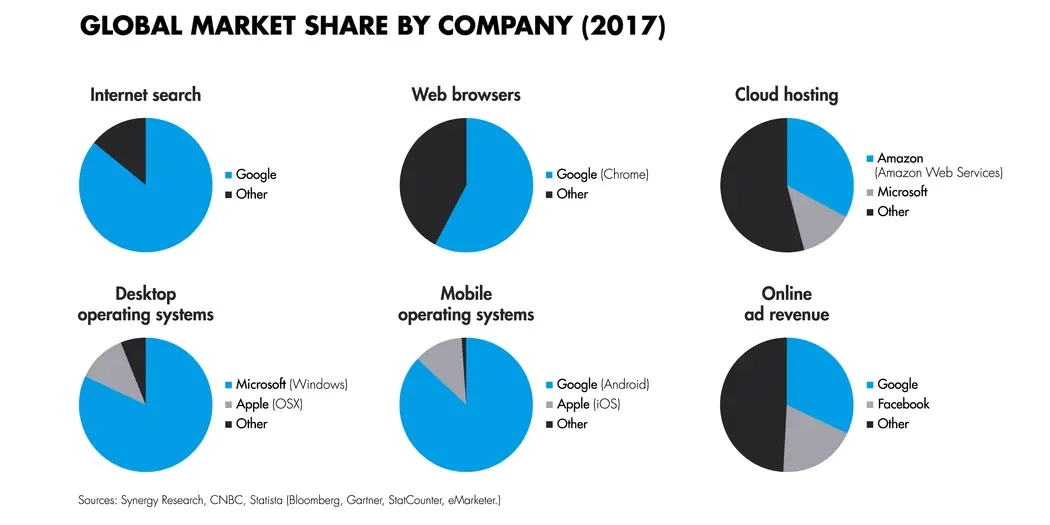

The rise of platform-based megafirms like Google and Facebook, he said, has seen digital markets shift more and more toward a winner-take-all dynamic, where the platform that attains dominance first tends to only need a slight edge over its competitors to harness powerful network effects and tip the market significantly in its favor.

“You see this concentration of megafirms across lots of sectors, like retail and logistics … and that raises issues about ‘Is this leading to a reduction in competition?’” said Van Reenen. “We think this may be a particular problem in digital markets, because they compete on platforms. People search a lot on Google, so Google gets more information and that improves their algorithms. Then, even more people use it, and that kind of snowballs and they monetize that through advertising.”

The tech giants’ reliance on enormous amounts of highly granular data to attract advertising revenue and improve their products has also sparked concerns about user privacy, with Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg appearing before Congress amid a data mining scandal earlier this year and a sweeping revision to how data is handled, the General Data Protection Regulation, going into effect in the European Union over the summer. Yahoo! Inc., which itself is owned by telecom giant Verizon, recently came under fire for its practice of scouring users’ email accounts for data that may be useful to advertisers—a tactic most of the company’s peers have shunned or stopped doing.

Late last month, U.S. President Donald Trump stoked the fires of the debate, claiming Google, Twitter, and other platforms were biased against conservative viewpoints, and said later that they “may be in a very antitrust situation.” He declined to signal whether he’d support breaking them up. In early September, Attorney General Jeff Sessions indicated antitrust action may be under consideration, as has Federal Trade Commission chairman Joseph Simons.

But applying too heavy a regulatory hand, some of these tech titans argue, could throw a wrench in the gears of innovation.

New approaches for a new technological age

MIT Sloan professor emeritus Richard Schmalensee worked as an expert witness for Microsoft on the landmark antitrust case brought against the company in 1998 and settled in 2001. Schmalensee said traditional methods of regulation aren’t likely to work on big tech firms like they have in the past for other industries, and concerns about their chilling effect on the march of innovation are well-founded.

Common forms of public utility regulation, including price controls like those imposed against electric and gas companies, won’t happen, nor would they make much sense for big tech companies, Schmalensee said. Attempts to break the megafirms up are unlikely to work either.

In the Microsoft case, U.S. regulators accused the company of engaging in monopolistic behavior by, among other things, bundling its Internet Explorer web browser together with Windows. The government initially argued that the company should be split, but the final decision was much less drastic.

Breaking up a company like Facebook, where the business model relies at its core on creating a large network to connect everyone on a single platform, could ruin the business itself and harm customers, Schmalensee said.

But some forms of antitrust regulation could take aim at the scale of those companies and their ability to retain market dominance. Take, for example, antitrust policy around mergers and acquisitions, Schmalensee said. Large companies often snap up smaller companies that could one day become a major competitor, acquiring their technology while eliminating the future threat.

“A lot of people have argued for being tougher on acquisitions,” Schmalensee said. “It’s not an extension of U.S. antitrust law or policy for that matter, to say ‘You really ought to be a little more skeptical of mergers, even with small companies, when they might grow into big competitors or have technology that can be used to make it difficult for others to compete.’”

Most of those firms are relatively small, with market shares to match, so their acquisition doesn’t usually trigger much scrutiny by antitrust authorities, Van Reenen said. Facebook’s 2012 purchase of Instagram for $1 billion in cash and stock stands as the classic example of the sort of forward-looking strategies regulators would need to detect and address.

“It’s very hard because it requires the antitrust authorities to take a view over how competition is likely to evolve in this marketplace,” Van Reenen said. “Maybe Instagram would never have got to be a big enough platform [to challenge Facebook].”

In that case, the deal was allowed to go through because Instagram did not sell advertising like Facebook did, regulators concluded. However, Facebook used the acquisition to drive even higher engagement with its platform, and engagement is what sells advertisements. Today, companies advertise on Instagram through Facebook’s advertising platform.

If the effect of mergers and acquisitions by large tech titans is that they’re blocking off future competition and innovation, then some regulation of the strategy could actually stimulate more innovation by giving small firms a chance to sink or swim instead of being immediately bought up by their larger competitors, Van Reenen said.

But while such acquisitions could have the effect of eliminating a potential threat to a large company down the road, taking too hard a stance against the practice could also stifle innovation, he said. When the rate at which companies are merging or making acquisitions is high, the chances a startup will get bought is also higher and the incentive for more entrepreneurs to launch one and begin to innovate follows suit.

“You’re trying to protect consumers by regulating, but then you can end up taxing innovation,” Van Reenen said. “The big companies say the reason we innovated so much is because of the rewards we expect to get, and if you basically start taking that away—taking away our intellectual property, it’s going to reduce our incentives to invest or for the next wave of entrepreneurs to come along.”

Schmalensee agreed: Closer scrutiny leads to higher levels of caution throughout an organization, and “being careful up and down an organization stifles innovation.”

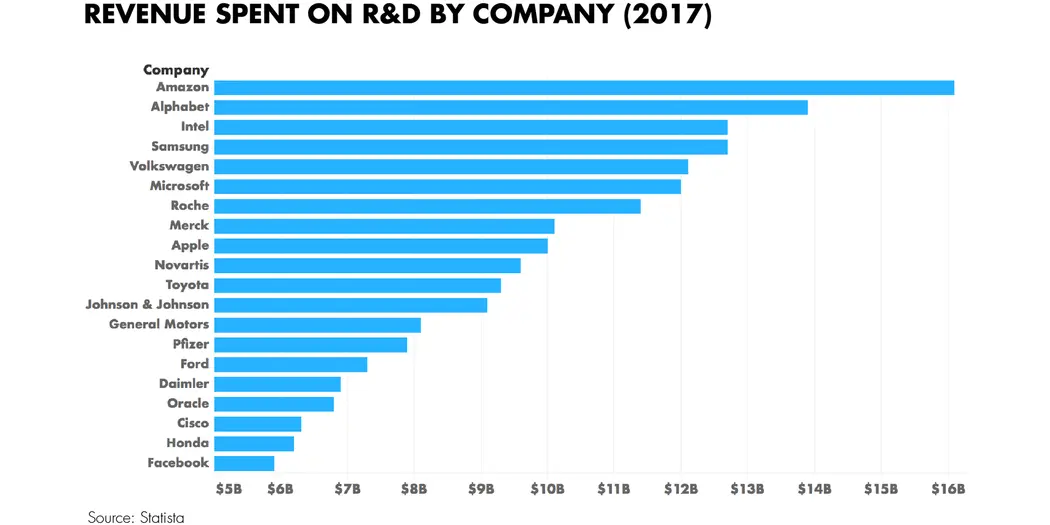

One way to approach the problem would be to shift the burden of proof that a merger or acquisition would benefit consumers and innovation to the company, rather than asking the antitrust authorities to prove it would not, Van Reenen said.In any case, the outcome is determined by whether the acquisition gives the smaller firm access to better resources, technology, and financing, or if the increased bureaucracy of a larger company blunts that firm’s motivation to innovate, Van Reenen said. Still, large tech companies are among the heaviest investors in new product development. Amazon invested more than $16 billion—the highest of any major company in the world—in research and development in 2017, while Alphabet, Inc., Google’s parent company, reinvested nearly $14 billion.

Pressure from across the pond

While the United States has been slower to take harder looks at these big tech companies, the EU and regulators from many of its member countries are pressing them to change policies that are believed to be in violation of antitrust laws or that pose concerns to user privacy.

Five of the most valuable companies in the U.S. economy—Alphabet, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft—have all faced regulatory action in Europe, and Van Reenen said that’s likely where the most pressure will continue to come from.

Google recently found itself the target of the single largest penalty ever levied by the European Commission, a $5 billion fine for unfairly favoring its own search services and other products on its Android mobile operating system.

The fine was similar to another record $1.3 billion settlement in a 2008 case brought against computer giant Microsoft by the commission for abusing the dominance of its Windows operating system. The commission again fined Microsoft more than $700 million in 2013 for failing to comply with the conditions of the previous settlement.

“The EU seems to be a lot more aggressive in pursuing antitrust policy against some of these tech titans,” Van Reenen said.

Schmalensee said that’s in large part because the EU has an antitrust law that targets a practice dubbed “abuse of dominance,” and that term can be broadly interpreted to include a galaxy of behaviors. “It’s always been an ill-defined thing,” he said. “Is charging a high price abuse of dominance? What is it?”

In the U.S., he said, most antitrust law is instead focused on making sure companies that come to dominate an industry didn’t obtain that position or defend it through anti-competitive or otherwise unlawful means.

But Van Reenen argued in a recent paper that even if a megafirm attains its dominant position without employing anti-competitive practices, there’s no guarantee that it will continue to use that power for the good of consumers.

“This does not mean antitrust policy should be relaxed,” he wrote. “[The firms] may well entrench their position through lobbying, erecting entry barriers, and buying up future rivals. As larger parts of the modern economy become ‘winner-take-most/all,’ it is important that competition authorities develop better tools for understanding harm to innovation and future competition, rather than the traditional emphasis on the pricing decisions of current rivals.”

What’s next?

As the tech titans continue to expand, scooping up promising startups along the way, expect the most aggressive pursuit of antitrust enforcement against them to continue coming from European regulators. However, all of the major tech firms discussed here are based in the United States, where it’s unlikely that we’ll see antitrust authorities pursue cases against them through traditional methods. Instead, the focus may be on scrutinizing merger and acquisition deals, and the jury is still out on what effect those may have on the pace of innovation.

Illustration: Rob Dobi