During World War II, as the Allies experienced shortages of food and basic goods, hoarding became a serious threat. A cartoon at the time showed a stern store manager confronting a shopper attempting to buy dozens of cans of food despite mandated rationing. Caught red‐handed, the shopper says, “I’m not hoarding, I’m just stocking up before the hoarders get here!

”Panic buying and hoarding are once again in the news, as fear induced by the pandemic strikes across the world. Images of people with shopping carts full of toilet paper and empty supermarket shelves have led to even more panic buying in a vicious cycle.

Toilet paper out of stock at a Boston area supermarket, March 16, 2020.

Credit: John Sterman

Why is this happening and what can we do about it? Is hoarding a rational, if anti‐social, response to scarcity, or an emotional reaction driven by fear and panic?

The Beer Game can help. Invented by legendary MIT engineer and management professor Jay Forrester in the late 1950s, the Beer Game is a rite of passage at MIT Sloan; I’ve been teaching it to our MBA and executive education students for nearly 40 years. Ironically, there is no beer in the beer game. Played on a table or online, participants take the roles of retailer, wholesaler, distributor, and brewer in a simulated supply chain. Players try to minimize costs while meeting customer demand. Deceptively simple, the game is far easier to manage than real supply chains: there are no capacity constraints, labor problems, or materials shortages. Consumer demand doesn’t fluctuate wildly, as we are seeing now. But participants—both students and experienced managers—always generate wild swings in orders and inventories, with average costs about ten times greater than optimal.

Playing the Beer Game at the MIT Sloan School of Management.

Credit: Brian Smith

Far more effective than any lecture on supply chains, the participants experience, first hand, how their own decisions create the boom-and-bust dynamics we are now seeing in products from hand sanitizer and medical masks to milk, eggs, and toilet paper.

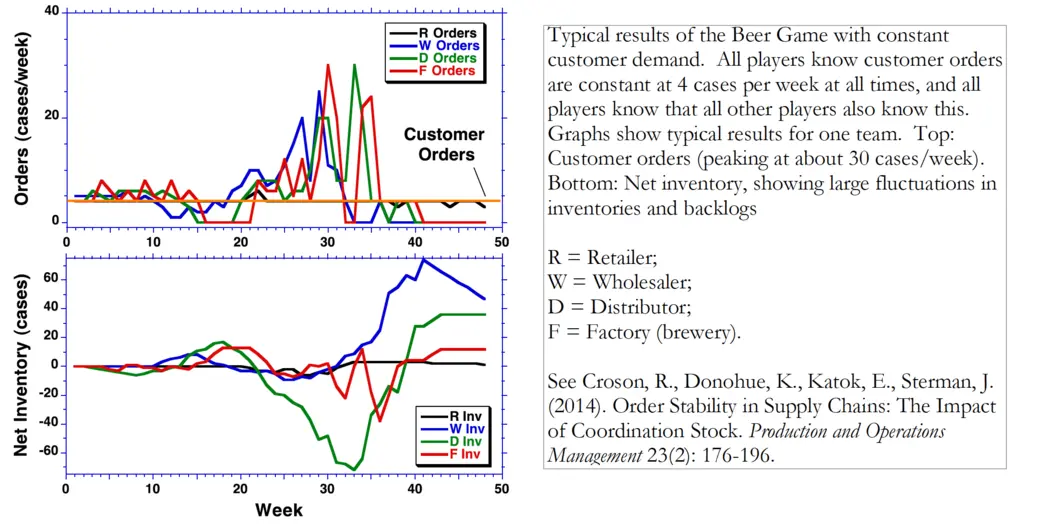

In experiments with the game going back to 1989, my colleagues and I have explored why people do so badly. In one study, we constructed a version of the Beer Game in which it is never rational to engage in panic buying or hoarding. Underlying consumer demand for the product was completely constant at all times. All participants knew this, and they also knew that all the other players also knew this. Prices were constant, so there was no possibility of price gouging. Each person had a single supplier, and each supplier a single customer, so there was no need to “stock up before the hoarders get here.” Under these conditions, everyone should have kept their orders constant, as you normally do—buying food and toilet paper only when you need to replace what you’ve recently used.

But that’s not what happened. Almost everyone ordered far more than they needed, then found themselves with too much and cut back their orders, generating repeated booms and busts throughout the supply chain.

Even more surprising, fully 22% of the participants placed orders more than 25 times greater than the known, constant customer demand. Not 25% larger—25 times larger. In a 2015 study, “I’m not hoarding, I’m just stocking up before the hoarders get here,” my colleague Gokhan Dogan and I explored how this could happen. The answer: hoarding and panic buying.

Here’s how the dynamics unfold: Some players initially ordered a little more than they needed. That unexpected increase in demand might cause their supplier to stock out. The supplier then places a bigger order with their own supplier, and so on up the chain. But it takes time to make and deliver the goods. In the meantime, some participants, worried that they were getting only a fraction of what they ordered, ordered still more, leading to even larger orders and bigger stockouts.

The panic feeds on itself: to protect themselves from unpredictable customers and unreliable suppliers, some players try to build up a safety stock. But the only way to do so is to order even more, worsening the shortage and reinforcing the belief among their supply chain partners that they themselves are unpredictable and unreliable. Trust erodes, stockouts and panic orders grow, and trust erodes further. These vicious cycles explode into massive shortages. Eventually, however, the brewery responds. A tidal wave of product floods the supply chain. People find themselves with far more than they need, and demand collapses. All this even though all participants know the underlying consumer demand is completely constant, and there is no rational reason to hoard.

Credit: John Sterman

We, and many other animals, evolved in a world of scarcity, uncertainty, and resource competition. In such a world, hoarding can be adaptive. Think of chipmunks and birds caching away nuts and seeds for winter; many species “squirrel away” their stash in multiple locations; some spy on others to steal their supplies; some check to see if others are watching before burying their own.

Brain imaging studies show that the impulse to hoard arises in our limbic system and amygdala, ancient structures that generate emotions, fight-or-flight, and other survival behaviors. For most people, most of the time, the evolutionarily recent frontal cortex, where executive decision making resides, suppresses the urge to panic and hoard.

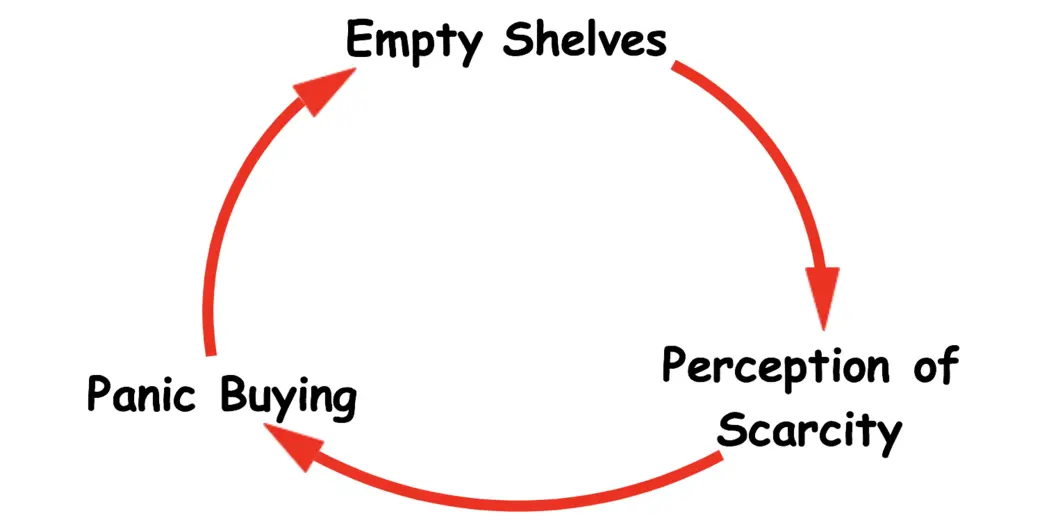

But the ancient impulse to get more now can dominate when we are stressed, for example by threats to our safety, health, and economy—stresses and fears greatly amplified by Covid-19. The perception of scarcity triggered by empty shelves then causes even more anxiety, leading some to buy as much as they can. These vicious cycles infect people with an irrational fear of shortages far faster than Covid-19 itself can spread.

Rest assured, there is no underlying shortage of toilet paper, cleaning supplies, or food in the United States. Our supply chains continue to function. Daily food consumption and toilet paper use are the same now as they were before Covid-19 hit. Hens are still laying and cows are still milked. Soon—and already in many places—empty shelves will be restocked. In the very near future, if it hasn’t already happened, there’s going to be plenty of toilet paper in the stores. Demand will collapse as people realize they really don’t need dozens and dozens of rolls. The implication: relax, and don’t buy more than you need. You’ll just end up wasting a lot as you find you can’t eat all that food before it spoils.

John D. Sterman is the Jay W. Forrester Professor of Management at the MIT Sloan School of Management and a Professor in the MIT Institute for Data, Systems, and Society. He is also the Director of the MIT System Dynamics Group and the MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative.

Although the underlying use of toilet paper hasn’t changed, the need for critical medical supplies, including gowns, masks, ventilators, and test kits has exploded, creating real shortages. Producers are working day and night to boost production. The workers making and delivering these supplies, and the health care providers who need them, are putting in extraordinary hours and effort, and we owe them a debt of gratitude.

So what can the rest of us do? Implement physical distancing and good hygiene for yourself. Urge your family, friends and colleagues to do the same, as soon as possible. You cannot wait until there are cases in your community because people become infectious before they exhibit symptoms. Support the stay-at-home policies now deployed across the country, including event cancellations, school closures, and bans on gatherings. Despite cabin fever, don’t stop isolation and distancing even after cases and deaths peak, and don’t pressure your friends, businesses or government to relax the restrictions. Help the disadvantaged and vulnerable in your community by volunteering to deliver food and other supplies. Cut your risk of exposure by going to the store less often and buying only enough to replace what you are actually using.

Collective, shared sacrifice by everyone today will lower the burden on the health care system and ease shortages of critical supplies, helping to protect our care providers so they can be there if you need them. But this isn’t just about you: You won’t just be protecting yourself, but those in high risk groups as well.