2 founders are not always better than 1

Solo founders are twice as likely to succeed in business as co-founders — maybe it’s time venture capitalists reconsider their assumptions about what makes a dream team.

Larry and Sergey; Jobs and Woz; Booz, Allen, and Hamilton (and Fry).

There are plenty of examples of successful co-founding teams, but research from Jason Greenberg, PhD ’09, and Ethan Mollick, PhD ’10 and MBA ’04, show the footsteps businesses should be following in are those of Jeff Bezos of Amazon, Sara Blakely of Spanx, and Oprah Winfrey.

In their recent working paper "Sole Survivors: Solo Ventures Versus Founding Teams," Greenberg and Mollick show that “companies started by solo founders survive longer than those started by teams.”

“It sounds like two heads should be better than one,” said Greenberg, today an assistant professor at NYU Stern. “Certainly they should have more resources: more human capital, more access to financial capital, bigger networks. But what that tends to ignore — particularly for early-stage ventures — is the extent to which there’s all sorts of social frictions that can occur when there’s more than one individual. To the extent that leads to diversions from productive activities to conflict resolution, the outcome may in fact be quite negative.”

The research is based on a survey of creators for thousands of Kickstarter projects between 2009 and May 2015. About 28 percent of the sample was made up of solo founders, 31 percent were two-person teams, and 41 percent were comprised of three or more members.

Credit: Laura Wentzel

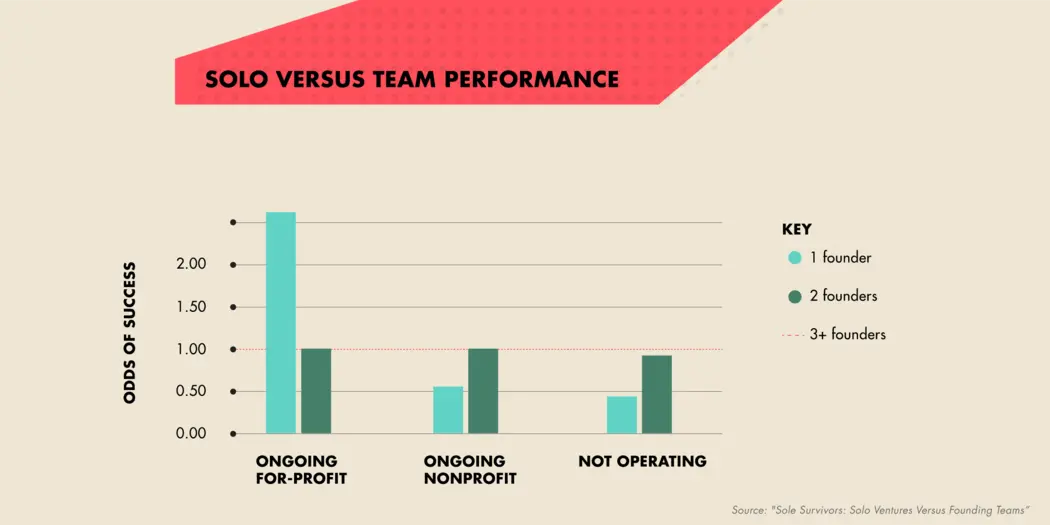

Solo founders are more than twice as likely to own an ongoing, for-profit venture than two or more founders. But solo founders are less likely to have ongoing, nonprofit ventures.

According to the researchers, ignoring other factors, solo founders are 2.6 times as likely "to own an ongoing, for-profit venture" than teams of three or more co-founders.

“This is also true when solo founders are compared to ventures founded by two founders [2.5 times as likely]," the study stated.

Greenberg said that compared to three-person teams, solo founders are 54 percent less likely to dissolve or suspend their business, and about 41 percent less likely to do so compared to two-person teams.

“Solo founders are, however, about 42 percent less likely to have ongoing nonprofits than three-person teams, and roughly the same versus two-person teams,” Greenberg said.

A perfect partnership

The research acknowledged that founding teams tend to take the spotlight for three reasons.

The first is that teams offer “fertile ground” for studying entrepreneurship and social sciences.Secondly, starting a business requires a variety of skills that few people possess all on their own, so having several founders would make representation of that entire skillset more likely.

Lastly, early research on solo founders suggested they underperform against teams, and not much has been done to disprove that early work, Greenberg said.

One 1990 study, for example, argued a larger founding team led to more successful semiconductor startups. But the argument compared large and small teams, and did not address solo founders.

“Other work has been used to make the same assertion, though actual analyses comparing the two outcomes are uncommon,” the report stated. “It is therefore unsurprising that the scholarly literature on startups increasingly entails the study of founders, plural.”

A “taken for granted-ness” has evolved around that sort of academic literature over time, Greenberg said. That, coupled with the “perfectly sensible” reasoning that a difficult process could be made easier with more resources and social support, creates “a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts.”

Venture capitalists have a mental model in place when they make an investment, and they start to look for teams with certain competencies, Greenberg said. Without any scrutiny around whether their assumption for a successful company is valid, that then becomes the de facto way of doing things, he said.

“I think it’s incumbent on the research community and certainly on the investors to the extent that their capital is at play, to test those assumptions and figure out when does this model work, when does it break down,” Greenberg said. “Ultimately they want their startups, their investments to be successful, and figuring out these sorts of issues should be of paramount importance to them certainly, but also for researchers trying to figure out how to structure early stage ventures.”

Greenberg said the hope is to highlight the fact that there are real world implications to shutting solo founded companies out of financial backing based on an assumption of the “superiority of teams.”

If it was just knowledge and resources that determined success, then teams would always win, the paper stated. But there are multiple social factors that contribute to a startup’s success.

“Disagreement, stress, and conflict are inevitabilities during the startup journey, and questions arise about how to address both opportunities and challenges,” the research stated. “When such disputes result in significant distractions from organizational development it becomes far from clear that a team is preferable to a solo founder.”

As for what’s next, Greenberg said he and Mollick (now an associate professor at Wharton), are already working on their next paper, which looks specifically at co-founding teams, and what factors determine their success and failure.