Labor

In cities, the escalator of opportunity has stalled

In cities, “employment polarization” has left those without a college degree behind. Minimum wage hikes and moves to high-opportunity neighborhoods can help.

At the turn of the 20th century, African Americans of the rural south, stifled under slavery’s shadow, commenced the Great Migration. North they went, drawn by the promise of Chicago, Detroit, Cleveland, and other cities.

Appalachians from Kentucky and West Virginia followed a similar trail in search of better jobs. Soon after, the dust bowl migration pushed farmers from Oklahoma, Arkansas, and elsewhere west to California.

Urban centers have long been viewed as hubs of economic opportunity, places where, regardless of background, you moved up from poverty to comfort.

But “there is limited reason to believe that this is still the case,” writes David Autor, an MIT economics professor and co-chair of the MIT Task Force on the Work of the Future. “The migration of less-educated and lower-income individuals and families toward high-wage cities has reversed course.”

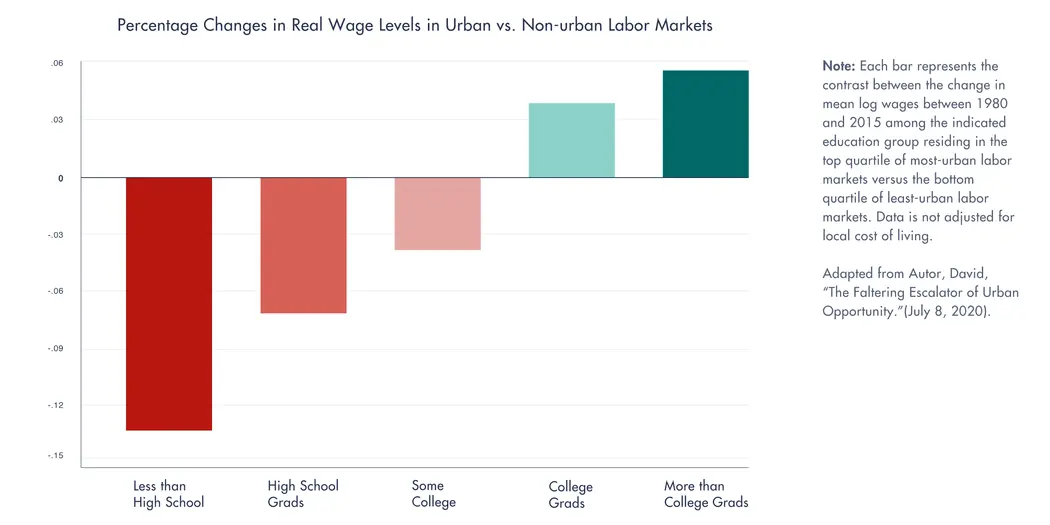

In a new report titled “The Faltering Escalator of Urban Opportunity,” Autor lays out the bifurcation in opportunity that arose among city dwellers between 1980 and 2015. Those with college degrees saw wage gains of as many as 6 percentage points compared to non-urban workers with college degrees; those without college degrees saw wages decline by as many as 13 percentage points relative to non-urban workers with a similar education level — a trend that saw Black men fare especially poorly.

At the heart of this change is a familiar story. After World War II, cities harbored a distinctive set of middle-class jobs reliant on skills and expertise, but not a college degree.

“Such jobs were comparatively scarce in suburbs and rural areas,” Autor writes, and they “provided an escalator of opportunity and upward mobility for immigrants, minorities, and workers who were less affluent and less educated.”

In the decades since 1980, under the joint pressures of automation and globalization, most of these jobs have vanished.

The result has been a process of “employment polarization,” through which educated urban professionals continue to capture high wages while those without a college degree, pushed out of stable, skills-based jobs, have dropped into low-paying service jobs; the urban wage premium that once made cities so attractive for those without a college degree has nearly halved since 1980.

“Non-college workers would have ample reason to reconsider the conventional wisdom that thriving U.S. cities offer a bastion of opportunity to all comers,” Autor writes.

The erosion of this wage premium contains a “distressing racial and ethnic dimension,” with Black men suffering the steepest drop in real wages, Autor writes.

Whites without a college degree have remained, for the most part, unscathed by a declining wage premium. For Black people without a college education, the decline was as high as 16 percentage points. (This drop was as high as 7 percentage points for Hispanics.) What's more, college-educated Black people in cities also saw a relative decline in wages in recent decades.

“Despite high levels of educational attainment, they exhibited downward occupational mobility in urban versus non-urban labor markets,” Autor writes. “Black, male college graduates are distinctive among college-educated workers in experiencing polarization with almost no accompanying upward occupational movement.”

For cities to remain attractive to those without a college education — more than half of residents in even the most well-educated cities — Autor proposes two policies. First, cities should increase the minimum wage, which, at the federal level, is currently lower than it was four decades ago. (Autor acknowledges that this is not a costless endeavor: consumers must absorb price hikes.) Second, cities should help families choose neighborhoods with good earnings opportunities relative to living costs. This could mean encouraging and supporting the move to less urban settings where wages have not stagnated.

The economic upheaval caused by COVID-19 makes these findings only more relevant. Shifts to remote work have dramatically curtailed demand for services, from restaurants and hotels to cleaning and maintenance. The more durable these changes are, the more dramatic the disappearance of even low-paying jobs for city residents without a college degree.

In short, Autor highlights the urgent need to address the fading appeal of cities for those without a college degree. And while housing prices are often blamed for this problem, they are not entirely to blame.

“While cities remain vibrant for workers with college degrees,” he writes, “the urban skills and earnings escalator for non-college workers has lost its ability to lift workers up the income ladder.”