Fintech

Fintech, explained

Successful fintechs possess four kinds of expertise: entrepreneurial, computational, financial, and regulatory. Here's how it all comes together.

Hear the word “fintech” and you’re apt to conjure up visions of young professionals day trading stocks, splitting the check with a payment app, and closing on a mortgage without setting foot in a bank.

Fintech — a portmanteau of “financial services” and “technology” — has certainly earned that stereotype: those applications are mobile-first, customer-centric, and disruptive to risk-averse industries, all hallmarks of modern fintech. But the industry’s reach is much broader, extending to the back offices and financial ledgers of banks, insurers, property management firms, government regulators, and more.

Globally, financial technology is projected to reach a market value of $305 billion by 2025, according to Market Data Forecast. That growth is fueled by rapid consumer adoption and by businesses — particularly small and medium-sized enterprises — turning to fintech for banking and payments, financial management, financing, and insurance.

For managing director of the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, fintech’s defining characteristic is its combination of technology and entrepreneurship.

“Fintech started when Michael Bloomberg started Bloomberg,” Aulet said. “Before that, there were financial services companies, but Bloomberg was a financial technology company. And it totally changed the game.”

To Aulet, who co-developed the MIT Sloan class “Fintech Ventures” with professorfintech means innovation coming from outside the walls of finance.

“Fintech companies are the people bringing technology to financial services. They’re showing ways to utilize technology to bring finance to a whole new level,” Aulet said.

Schoar, who specializes in consumer and entrepreneurial finance, said fintech startups thrived after the 2008-09 stock market crash, when banks were under an increased level of regulatory scrutiny that startups weren’t subject to. But established institutions are catching on, and catching up.

“Right now, the majority of spending on what we call fintech activity is actually in big banks,” Schoar said.

Fintech going forward will be defined by data and access, Schoar said. Machine learning will deliver more specific insights from ever bigger datasets, while ubiquitous mobility “allows for instant access to the consumer, and for consumers, instant access to their own data.”

And with millennials and Generation Z increasingly at the helm of startups, concerns over environmental, social, and governance policies are increasingly part of the fintech equation.

“I'm very mission-driven,” said Gabrielle Haddad, MBA ’17, co-founder and chief operating officer at Sigma Ratings, which offers an intelligence platform to help banks, corporations, and governments assess the reputational, operational, and financial crime risks of their counterparties. “I'm inspired by the fact that financial services are really the gateway to greater social and economic opportunity, and social progress.”

Entrepreneurship Development Program

In person at MIT Sloan

Register Now

Fintech explosion

MIT Sloan professor of the practicewho taught “FinTech: Shaping the Financial World,” favors a broad view of the sector, one promoted by the Financial Stability Board, a global advisory body.

“It’s any technology that's changing business models in finance in a material way,” Gensler said in a July 2020 interview. President Biden in January nominated Gensler to lead the Securities and Exchange Commission.

“Fintech is a word that's been used in the last 20 years by venture capitalists and startup entrepreneurs, but it goes back thousands of years,” said Gensler, the former chair of the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

He offered his students a timeline in innovation that moves from negotiable checks in the 1500s through mobile wallets and chatbots. “It really goes back to the invention of money,” he said.

Gensler said that three developments from the mid-1990s gave birth to modern fintech: the internet, mobile phones, and the cloud. It’s no coincidence that Amazon and eBay were both founded in 1995, with PayPal following a year later.

“1996 was a really important year, because we figured out how to secure commercial transactions on the internet, how to move packets of data around in a cryptographic way,” Gensler said. “And all of a sudden, a whole bunch of things start to shift and change.”

The fintech market segment today is “incredibly broad,” said a visiting associate professor of finance, and managing partner at venture capital firm Tectonic Ventures.

“Fintech is any company using technology to support financial services of any type,” Rhodes-Kropf said — which can include regulatory tech, lending, payments, saving, investing, insurance, robo-advice, accounting, risk management, claims processing, and underwriting.

In payments, PayPal has been joined by startups like Square, Stripe, Toast, Plaid, and TransferWise, which made it easier and less expensive to transfer money internationally; in credit, Lending Club, Revolut, SoFi, and Kabbage grabbed attention and market share.

“Insuretechs” like Assurance, Goji, Root, and WeFox made inroads in the insurance market, while robo-advisers from Betterment, Wealthfront, and Ellevest attracted customers with inexpensive, algorithm-driven investing advice.

As the fintech movement matures, the focus is shifting somewhat away from customer-facing apps to address the industry’s thornier problems — cybersecurity, specifically anti-cyber-fraud, and “regtech,” which seeks to automate and streamline the complex regulatory landscape that financial services organizations must traverse, Rhodes-Kropf said.

Finance’s technology stack

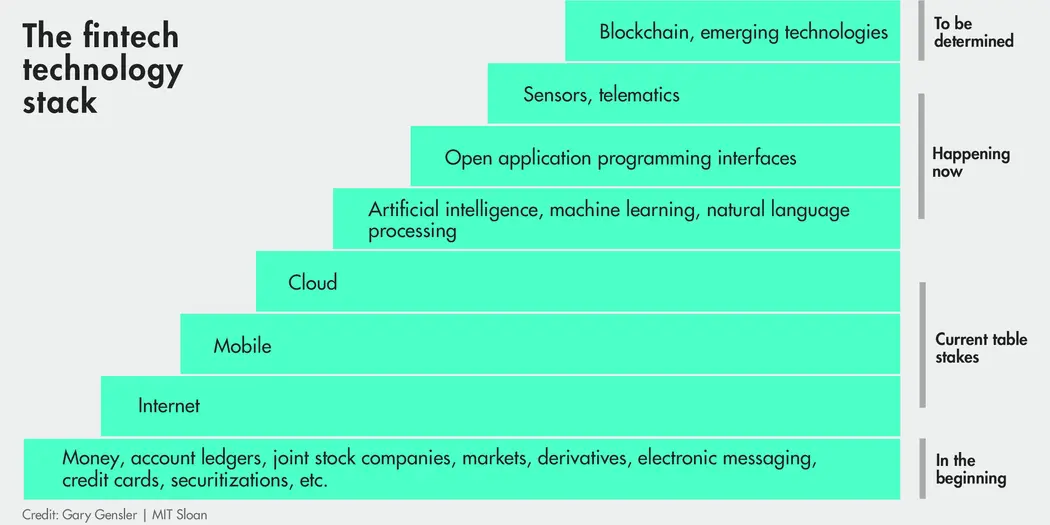

All that innovation was and is built on a finance technology stack that’s still evolving. In Gensler’s view, it looks something like this:

The industry is at the point where the internet, mobile, and cloud computing are table stakes, even for established players that more slowly adopt technology. Gensler said innovation in the next five to eight years will come from artificial intelligence, machine learning, and natural language processing — technology that extracts and analyzes data from language-based sources like white papers, earnings reports, press releases, and social media.

Open application programming interfaces allow third parties to access data traditionally held by large commercial banks, while sensors and telematics are remaking the auto, health care, and property insurance markets.

Blockchain, the distributed-ledger technology behind Bitcoin and other digital currencies, is a question mark at this point, said Gensler, who served as a senior adviser to the MIT Digital Currency Initiative and taught “Blockchain and Money,” available from MIT OpenCourseWare.

“We’re not sure when that will come into the technology stack. I'm not sure it will fully come in,” Gensler said. “But it's definitely a catalyst for change.”

The 4 pillars of fintech success

Aulet, who oversees the Trust Center’s annual delta v venture accelerator competition, said fintechs have to master four areas of expertise to succeed:

- Entrepreneurship. Disciplined companies that have a clear, quantitative value proposition stand a better chance at success.

- Technology. Growth and opportunity in the fintech market will come primarily from strategic deployment of AI, machine learning, natural language processing, and advanced sensors and robotics, and that’s on top of the computing knowledge needed to manage and strategically exploit financial services’ enormous datasets.

- Domain knowledge. Finance is the most lucrative, and arguably one of the most complex, sectors of the economy. Startups without deep knowledge of the industry will struggle to identify viable opportunities and sustain credibility.

- Policy and regulation. As with the energy and biotech markets, government regulation plays a significant role in finance, one that startups downplay at their peril. “You can't do fintech and ignore the policy ramifications of it,” Aulet said.

Haddad seconded Aulet’s assessment.

“You have that huge regulatory piece, and it does add a real layer of complexity,” Haddad said. “Any time you're trying to innovate in a highly regulated space, having an understanding of regulation is going to be really essential.”

Other startups with MIT connections that have had notable success in checking off all the boxes include FutureAdvisor, an automated investing service now owned by BlackRock; CoverWallet, which offers insurance coverage to small and medium-sized enterprises tailored by market segment; Flywire, a global payments firm; and Ricult, which makes digital financial tools designed to help rural farmers in developing countries avoid financial exploitation.

The competitive landscape

Fintechs share another characteristic with startups in biotech and energy technology: They don’t “disrupt” their industry in the way that, say, Uber disrupted the transportation sector, but rather develop value propositions in unique niches among and between much larger players.

“Biotech firms develop wonderful new drugs and, for the most part, large pharma buys them,” said Rhodes-Kropf. In the same way, “fintech is disruptive, yes, but not in the sense that some new tech-enabled investment bank is going to make Goldman Sachs go away.”

That’s because financial institutions — think Fidelity Investments Inc., Vanguard, Citigroup, and JPMorgan Chase & Co. — are enormous, well-capitalized, and more than able to absorb challenges, either by buying startup technology they like (CoverWallet was acquired in January 2020 by Aon Plc), or developing their own.

In recent years, Big Finance and especially Big Tech have been aggressive in rolling out competing products in payments, credit, and robo-advising, further muddying the waters.

“One of the biggest payment companies in the world is Alibaba, a tech company,” Gensler said. “Apple, Google, Facebook, and to some extent also Amazon are all in the payment space where you can both get a customer interface and data. Apple combined with Goldman Sachs and MasterCard to roll out the Apple Credit Card. Facebook is offering Libra … do you call that fintech or not?”

To survive amid such well-funded and omnipresent giants, would-be entrepreneurs need to understand both established finance and technology players and look for spaces to add value, Gensler said.

“It's the three communities competing," Gensler said, "and the startups are trying to think ‘What cracks are there? What can we do better, cheaper, faster? How can we give somebody a better user experience?’”

The regulatory landscape

Crystal ball predictions in venture-heavy markets are never easy, more so when a global pandemic and shifts in political power are in play. On the regulatory front, signs are mixed, said Laura Kodres, a past distinguished senior fellow of the Golub Center for Finance and Policy at MIT Sloan. Up until now, governments in the U.S. and parts of the European Union have been cautious, trying to fit fintech into existing regulatory structures and offering one-off accommodations to companies wanting to skirt the rules.

Related Articles

Other countries initially took a more open approach, only clamping down when they saw consumer protection issues, cyber risks, or fraud emerging, as happened in China in 2016 and again in 2019 when many of the peer-to-peer lenders that had sprung up in the country were found to be predatory.

Now, Kodres said, many countries have moved to a middle ground of a “controlled experimentation” approach, with government-sponsored incubators and sandboxes, such as those in the U.K. and Singapore.

In the U.S., the Biden administration will be confronted with some difficult choices, said Kodres, who previously worked at the International Monetary Fund.

There is a desire among many of Washington’s financial policymakers to ensure financial services are more widely available to all income groups, known as financial inclusion, Kodres said. But that goal may be best achieved through the network advantages and data collection prowess of Big Tech, a sector whose practices are currently under intense scrutiny.

A more immediate concern is consumer protection.

“There is a concern that people gamble away their entire savings in the stock market without understanding what they are doing,” said Schoar, who has published research showing that credit card companies are more likely to target less-educated consumers with shrouded “back-loaded” features such as high-default annual percentage rates, and late or over-limit fees.

Concern heightened in late January, when the popular stock trading app Robinhood became one of the engines used to run up the stock of GameStop. The event, which pitted day traders against some of Wall Street’s largest hedge funds, raised alarm among regulators and consumer advocates concerned that retail investors did not fully understand their financial exposure.

“The truth is that many of the small investors who look like winners after pushing up shares of GameStop could soon become losers,” New York Times financial columnist Andrew Ross Sorkin wrote on January 28.

On the flip side, some users who contended they did know what they were doing felt betrayed by Robinhood’s decision to restricted trading on certain social media-fueled stocks in the days following the initial runup.

“After becoming the venue of choice for small investors, the app risks alienating a core customer base,” Sorkin wrote the next day.

Even before the GameStop incident, Robinhood had been fined by the SEC for failing to inform clients it was selling their stock orders to trading firms and accused by one state regulator of using “aggressive tactics to attract inexperienced investors” and “gamification strategies to manipulate customers.”

Robinhood may be the most prominent example of the debate over consumer protection, but it’s not the only one, market watchers agree.

“The disintermediation of financial services through fintech exposes people who are not financially literate to a lot of risk,” Schoar said.

Forecast 2021 and beyond

How has fintech fared in the COVID-19 pandemic and the economic chaos it unleashed? At the outset, the pandemic helped some fintech niches, particularly digital payments, while sidelining others, including digital lending.

“We had three or four companies that were doing unbelievably well because of COVID-19, and we had a couple of other companies that were doing disastrously,” Rhodes-Kropf said. “We asked each one of our businesses to go through and think about how they could be relevant. That could mean [anything from] shifting messaging slightly to really fundamentally rethinking their value proposition.”

Related Articles

Now the market has snapped back.

“Tech in general is just extremely hot,” Rhodes-Kropf said. “With interest rates at record lows due to a savings glut, investments that pay off far in the future are in demand,” which is good news for most fintech ventures.

Sigma Ratings’ Haddad said she believes the pandemic has increased opportunities for fintech overall. “We're living in a digital-first world now. There are opportunities for fintech companies that are able to do things faster in a more consumer-friendly manner,” Haddad said.

As for companies like hers, which deal directly with banks, the atmosphere of cost-consciousness prompted by persistent low interest rates presents an opening as well.

“Our solution is meant to reduce risk while helping to drive efficiencies and cost reduction for banks,” Haddad said. “With everyone focused on cost-cutting, there's a real opportunity to step in now and say, ‘How can bringing in a new technology solution help you to do that?’”