Machine learning will redesign, not replace, work

It’s time to shift the conversation around AI and machine learning from threats of job replacement to opportunities for job redesign.

The conversation around artificial intelligence and automation seems dominated by either doomsayers who fear robots will supplant all humans in the workforce, or optimists who think there’s nothing new under the sun. But MIT Sloan professor Erik Brynjolfsson and his colleagues say that debate needs to take a different tone.

New research finds that specific tasks within jobs, rather than entire occupations themselves, will be replaced by automation in the near future, with some jobs more heavily impacted than others.

“Our findings suggest that a shift is needed in the debate about the effects of AI: away from the common focus on full automation of entire jobs and pervasive occupational replacement toward the redesign of jobs and reengineering of business practices,” the researchers write in an article published in May in the American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings.

The work is by Brynjolfsson, professor Tom Mitchell of Carnegie Mellon University’s machine learning department, and Daniel Rock, a doctoral candidate and researcher at the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy.

“Despite what Hollywood is saying, we’re very far from artificial general intelligence. That’s AI that can just do everything a human can,” Brynjolfsson, who teaches an online MIT Sloan Executive Education course on digital business strategy, said. “We don’t have anything close to that. We won’t for decades, unless there’s some amazing breakthrough.”

What we do have are powerful narrow AI systems, Brynjolfsson said, which are capable of solving certain, specific problems at human or super-human levels of accuracy, typically using deep neural networks. Those technologies are adept at tasks involving predictive analytics, speech and image recognition, and natural language processing, among others.

“But that’s not everything — it’s some things,” he said. “That raises the obvious question: what are the tasks that this amazing AI can do well, and which are the tasks they can’t do?”

To answer those questions, the researchers developed a 23-question rubric to determine whether a task is suitable for machine learning. How high or low a task’s score is on the rubric indicates how susceptible it may be to automation and machine learning, Brynjolfsson said. He and Tom Mitchell published the original rubric in the journal Science in December, 2017.

“Any manager could take this rubric, and if they’re thinking of applying machine learning [to a task] this rubric should give them some guidance,” he said. “There are many, many tasks that are suitable for machine learning, and most companies have really just scratched the surface.”

The researchers wanted to take the idea further. Since a job is just a bundle of various tasks, it’s also possible to use the rubric to measure the suitability of entire occupations for machine learning. Using data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics, that’s exactly what they did — for each of the more than 900 distinct occupations in the U.S. economy, from economists and CEOs to truck drivers and schoolteachers.

“Automation technologies have historically been the key driver of increased industrial productivity. They have also disrupted employment and the wage structure systematically,” the researchers write. “However, our analysis suggests that machine learning will affect very different parts of the workforce than earlier waves of automation … Machine learning technology can transform many jobs in the economy, but full automation will be less significant than the reengineering of processes and the reorganization of tasks.”

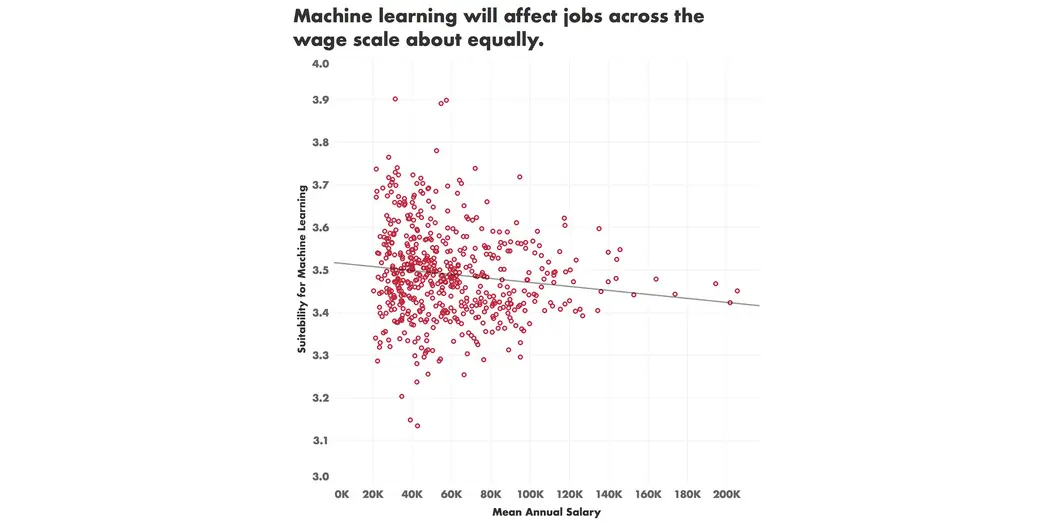

The impact from the current wave of automation, driven by machine learning technologies, can be expected to affect jobs across the wage scale about equally. It will most likely see tasks within jobs replaced while occupations themselves are redesigned, not eradicated. Data: Erik Brynjolfsson and Daniel Rock (MIT Sloan,) Tom Mitchell (Carnegie Mellon) - 2018.

Radiologists, for instance, have 26 distinct tasks associated with their job, Brynjolfsson said. Reading medical images is a task well-suited for machine learning, with computers starting to become better at image recognition than humans. But interpersonal skills like conveying health care information to a patient are not as easily or effectively performed by machines, he said.

“In almost every occupation, there are at least some tasks that could be affected, but there are also many tasks in every occupation that won’t. That said, some occupations do have relatively more tasks that are likely to be affected by machine learning” Brynjolfsson said, noting that a job like a concierge could be, and is being, mostly replaced by services based on machine learning from companies like Google.

Jobs like massage therapists, which don’t have much potential for machine learning, are likely to be the least affected, according to the study.

The researchers recommended looking at the tasks within each occupation that have high potential to be automated by machine learning, separating them from the tasks that do not, and reorganizing the job to match those developments. Machine learning could be doing the tasks it is ideal for, they write, while human labor could be freed up to do more of the activities machine learning is not well-suited for, with a net effect of increased profitability.

That’s not to say new developments in machine learning couldn’t have a wider impact on jobs and the economy in the future, the researchers write.

“Matching the evolving state of the art in ML in the future will require updating the rubric accordingly,” they write.