When Asha Seth Kapadia, SM ’65, came to what was then called the MIT School of Industrial Management in 1963, she was one of six women enrolled as a graduate student in Course XV.

“I was the only woman in all the classes I took at MIT,” she said in a 2014 interview with the Texas Medical Center Women’s History Project.

Asha Seth Kapadia, SM ’65

Kapadia, who passed away in 2021 at the age of 83, was one of 31 women to receive undergraduate and graduate degrees at MIT’s 99th commencement on June 11, 1965, and one of the first women to earn a master’s degree in industrial management from the business school. At the time, women comprised less than 5% of the entire student body.

Almost 60 years later, both the Institute and the long-since-renamed MIT Sloan School of Management have demonstrated significant, ongoing efforts to increase the quantity and quality of opportunities for women students, faculty, and staff. At the 2022 MIT Sloan Women’s Conference, Kathryn Hawkes (Senior Associate Dean, External Engagement) celebrated the MBA Classes of 2023 and 2024, which are comprised of 44% and 48% women, respectively.

Throughout her accomplished career as a faculty member at the University of Texas School of Public Health in Houston and her advocacy for women’s rights, Kapadia kept track of these developments and more. She expressed her encouragement with the school’s progress in a 2010 interview with the alumni magazine, explaining that she wanted MIT Sloan to do for other women what it had done for her.

“Going to MIT Sloan was the best thing I ever did,” she said. “I have met the most fascinating people across the Institute, and many have become lifelong friends and colleagues.”

Early life

Asha Seth Kapadia was born on August 16, 1937, in the city of Lahore in what is today Pakistan, just one day shy of a full decade before the partition of India.

The creation of two countries at midnight on August 15, 1947, resulted in a great deal of confusion for many on either side of the newly erected border. As a result, Kapadia’s family had to pack everything they could and flee their home in the middle of the night.

“All the paperwork was left,” she said. “We just ran with whatever we were wearing.”

After arriving in India, Kapadia’s father took her and her sisters to register for school. Education was very important to her family—especially her mother and father, who were both highly educated. They went to great lengths to encourage their daughters to pursue higher education.

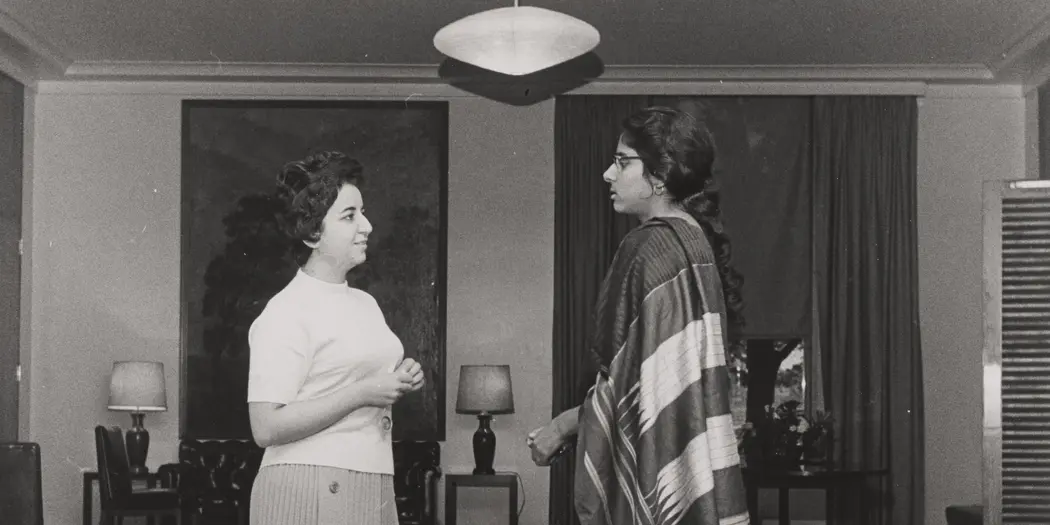

Hanna Kheir-El-Din, PhD ’76, and Asha Seth Kapadia, SM ’65, stand in the foyer of the newly opened women's dormitory Stanley McCormick Hall in 1963.

Credit: Courtesy MIT Museum

They were also fierce advocates for women’s liberation in India. As Kapadia’s son, Dev Kapadia, recalls, his grandparents instill in their daughters a strong sense of equality in an otherwise unequal world.

“They drilled it into all five of their heads that they were equal: ‘There’s no difference between you and a man,’” he says. “[My mother] was born in the 1930s and grew up in the 1940s and 1950s, and this was not what people were taught in India back then, but nobody was going to tell her she couldn’t do something just because she was a woman. I think all of that is the genesis for her advocacy for women’s rights.”

As Kapadia put it in 2014, “I had to push myself because I’m not an aggressive person. I’m kind of mousey in many ways, I keep quiet, but I said to myself, ‘Who else will fight for me?’”

Choosing MIT

Kapadia’s father originally wanted to study at Oxford or Cambridge but pursued his education locally while staying home to care for his ailing father. Attending those schools remained an “unfulfilled ambition” of his, Kapadia explained, and he did everything to encourage his daughters to apply to both schools.

While studying mathematics at Delhi University, Kapadia ranked first in her undergraduate and graduate classes. She then applied to Oxford, Cambridge, Stanford, and Harvard, and was admitted to all four. She also received a prestigious national scholarship to study mathematics and the sciences from the Indian government. Kapadia was the only award recipient that year.

Thanks to a conversation about MIT with an alumnus, however, Kapadia was not interested in Oxford or Cambridge. “I wanted to come to MIT,” she said, and despite accidentally missing the admissions window, she refused to take “no” for an answer. She wrote to the admissions office and, among other things, included a copy of her Harvard admission with her letter.

“And can you believe they admitted me?” Kapadia said with a laugh. “So, I went to MIT.”

Kapadia arrived on campus to find a “very rich environment” for her interest in mathematics, but a potentially isolating one as an Indian woman. Not only was she often the only woman in the classroom, but she also typically wore traditional Indian saris, which caused her to stand out even more. Despite all this, Kapadia never felt isolated.

She befriended many of her business school classmates, developing personal and professional relationships that would last throughout her life. Additionally, Kapadia got to know the other inaugural residents of the new women’s dormitory, Stanley A. McCormick Hall, named for the husband of women’s rights activist and philanthropist Katherine McCormick, Class of 1904.

“The other students I met became good friends with me. We enjoyed doing things together and I never felt homesick,” she said. “Those two years were the best years of my life. I ended up learning a lot from MIT.”

Introduction to public health

With guidance from her thesis advisor, operations research luminary John D.C. Little, SB ’48, PhD ’55 (Institute Professor Emeritus), Kapadia studied queueing theory, the mathematical study of queues or waiting lines. As a research subject, it has proven especially prudent for managers when making decisions about resource allocation for services rendered.

After graduating from MIT, Kapadia joined the statistics department at Harvard, where she wrote a doctoral dissertation on queueing system dynamics. She later worked for Arthur D. Little’s management sciences division in Cambridge, where she was first exposed to public health on a project building a rubella outbreak model.

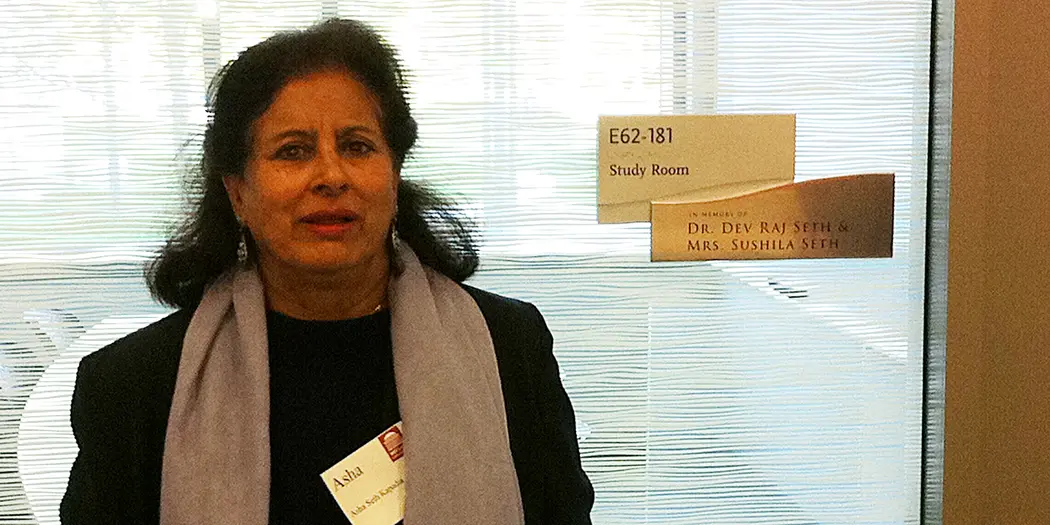

Asha Seth Kapadia, SM ’65, poses with E62-181, the room she dedicated to her parents, Dr. Dev Raj Seth and Mrs. Sushila Seth.

Credit: Courtesy Dev Kapadia

This fomented a desire in Kapadia to merge her management science and statistics experience with the social science of healthcare. So, when her then-husband got a job offer in Houston, she left the Cambridge firm and took successive positions at the University of Houston, Rice University, and the University of Texas School of Public Health, where she would remain for the rest of her career.

“I was the only woman faculty member in the biostatistics department at that time, but I had wonderful colleagues there and I learned a lot,” said Kapadia.

She quickly expanded her doctoral research on queueing theory and statistical techniques to issues with kidney transplant systems, healthcare cost models, and more. In addition, Kapadia also became a driving force in the department and across the school, both for the colleagues she worked with, the students she mentored, and those who fit into both camps.

“Asha stood out. [She was] forthright, confident, brimming with intelligence, elegant, proud of her culture, humorous, curious, welcoming, [and] unafraid of setting high standards for her students,” Patricia Mullen, a former colleague, said in 2022.

Lem Moye, a retired biostatistician and data science educator, remembers his professor and mentor as someone who treated him as a peer.

“It was easy to be open and honest with Asha, and it was very difficult to say no to her. She took the point of view that the endeavor she wanted you to be involved in was in your own best interest,” he says. “That’s actually very powerful. She did that with me, and she was right.”

Kapadia received tenure in 1976, became a full professor in 1984, and was appointed faculty chair in 1996. She also served on many school committees and received visiting professorships from universities in India and Mexico, but she never forgot her roots at MIT.

Talking to the future

Of the volunteer opportunities available to alumni, one of the most popular, and most necessary, is the Educational Council. Managed by Yi Tso, SB ’85, in the MIT admissions office, the council consists of educational counselors around the world who recruit, interview, and respond to the concerns of admissions candidates in their respective communities.

Kapadia became an educational counselor in Houston when Greg Turner, SB ’74, MArch ’77, who went on to become MIT Alumni Association president in 2011, was the regional coordinator.

“She was a star. Whenever you needed something or had a particular challenge—for instance, if another educational counselor couldn’t interview that year or something like that—Asha was always ready, willing, and able to pick up the slack,” he says. “I just can’t say enough good things about her.”

As longtime alumni volunteer Laurie Gavrin, SB ’83, has said of being an educational counselor, “You’re talking to the future, and the future talks back.” Those who take on this role serve as ambassadors for MIT to prospective students and their families, and as Turner, his successor Ed Rinehart, SB ’64, PhD ’70, and others remember, Kapadia enjoyed every opportunity she had to do just that.

The E62-181 study room today, which is located in the MIT Sloan Executive Education suite.

Credit: Andrew Husband

“She loved doing those interviews,” says Dev. “She would meet somebody, then come home and excitedly tell me all about them.”

During her final years as an educational counselor, Kapadia was assigned to the Michael E. DeBakey High School for Health Professions. Located in the heart of Houston’s Medical Center, it is the city’s only magnet school for health professions, which made it the perfect place for Kapadia to marry her volunteer work with her role as a public health professional.

“I’ve been interviewing some amazing students [from DeBakey]. I can’t believe kids like that exist!” she exclaimed in 2014.

The sky’s the limit (if you are grounded)

Again and again, former students and colleagues, fellow volunteers, and others have recalled the distinctly warm and erudite way Kapadia was able to provide mentorship and comradery as an educator, a collaborator, and a friend. Her example was both a comfort and a guidepost.

Mullen praised her for “her navigation of personal and professional spheres,” which “paved the way for those of us to follow.” Kapadia’s son could not agree more: “She was able to do what she did in her career while also making me a priority. She made our entire extended family a priority. Honestly, in today’s world, it’s hard to do both, but she was able to do it.”

When asked about this by the Texas Medical Center Women’s History Project in 2014, Kapadia declared, “The sky’s the limit if you are grounded… If you are grounded and willing to work honestly and work hard, how can you go wrong?”

She went on to say that her life at MIT, Harvard, the University of Texas School of Public Health, and everywhere before, in between, and after had been excellent, but not without its share of ups and downs.

“But that’s okay because we must be tough to live. Nobody’s life is smooth like this,” she told the interviewer while motioning her hand in a straight line. Changing it to a curvy motion, like the peaks and grooves on a line graph, Kapadia concluded, “It’s always like this.”

Asha Seth Kapadia was one of many alumni featured in the exhibit South Asia and the Institute: Transformative Connections, which ran through October 13, 2023, at the Maihaugen Gallery. Read more about the exhibit at MIT News.