MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy

Public Policy

Tailoring Bank Regulations: How Did the Market React?

The 2008 financial crisis triggered a wave of new financial regulations, most notably as mandated by the Dodd Frank Act of 2010. That legislation recognized that existing regulations were inadequately designed to protect against systemic risk and reflected the desire to prevent any recurrence of bailouts and financial system disruptions. To that end, it required regulators to create over 200 rules aimed at ameliorating various aspects of risk.

A decade later, amid concerns from financial institutions and some commentators that the burden of some of those new rules exceeded their stability benefits and were generating unintended consequences, Congress and regulators are revisiting some of those decisions. In 2018, Congress passed, and the President signed, the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act that provided US Bank regulators with authority to tailor bank regulation to the risk posed by the bank. On October 10, 2019, the Federal Reserve Board, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) issued final rules that relaxed regulatory standards for those banks that are designated “Tier 3 and Tier 4 Banks.” Generally, these are banks with assets between $100 billion and $700 billion, although other factors such as international operations and short term funding play a role in the classification. The regulatory relief came in the form of lower liquidity requirements, relaxed capital standards, and a lessening of the frequency for submitting “living wills.” The large banks that were designated Globally Systemic Important Banks (GSIBs) are Tier 1 Banks and saw no regulatory relief. The Fed’s summary of the changes and the tiering of the banks is available here.

This bifurcation, with some banks given what appears to be significant regulatory relief and others none, allows us to address the question: Did the market view this deregulation as a boost to future bank profits? If the market expects these changes to result in reduced costs or increased revenues for the Tier 3 and 4 Banks, we would expect these banks to have outperformed the GSIB banks or other financial companies. To address this, we look at stock performance for the banks over two periods. First, around the time of the publishing of the final regulation in October 2019. Second, from the time the rules were proposed in October 2018 to today.

Did the publication of the final rule result in gains for Tier 3 and 4 Banks relative to either GSIB banks or the S&P Financials?

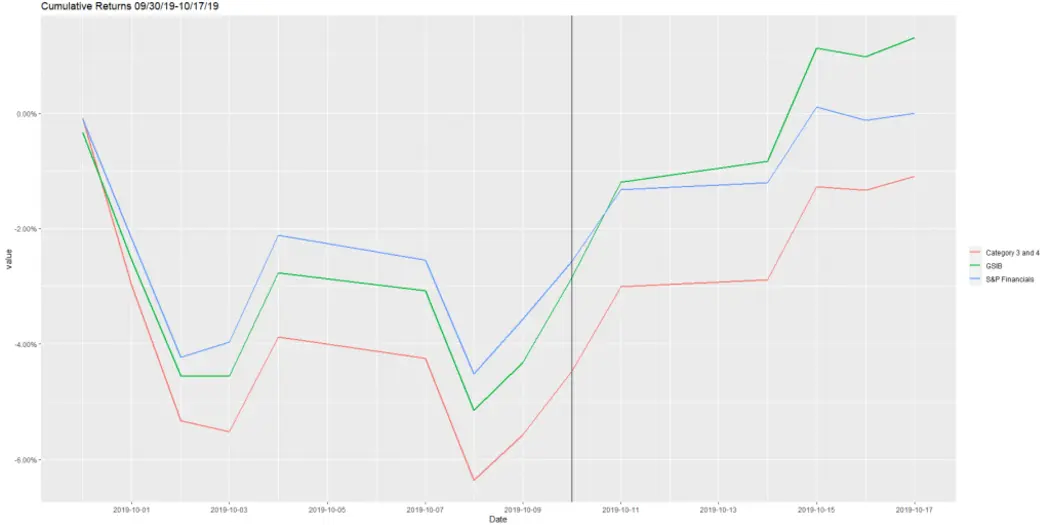

Figure 1 shows the cumulative returns for the three groups. Over the first three weeks of October, the GSIB banks outperformed the S&P Financials by 1.31% while the Tier 3 and 4 banks underperformed S&P Financials by 1.10% and the GSIB banks by 2.41%. If one focuses just on the period three days before the announcement to three days after, the results are similar with Tier 3 and 4 banks underperforming the GSIB banks by 1.24%.

The Federal Reserve published the final rule on October 10. The publication should have been viewed as beneficial to Tier 3 and 4 banks in that it reduced the uncertainty by finalizing the previously proposed rule. Of note is that little of substance changed between the proposal and the final rule. The fact that there were negative, not positive, returns for Tier 3 and 4 banks relative to GSIB banks, is broadly consistent with two hypotheses. Either the market did not view the regulatory relief as significant, or the information about the regulatory relief was already reflected in stock prices before the publication of the final rule. To try to distinguish between these two hypotheses, we look at the returns since October 2018 when the proposed rule was published.

The cumulative returns for the three groups. The portfolios are cap-weighted. The black line is the date of the final tailoring rule announcement. The final difference between the GSIBs and the S&P Financials index is 1.31%. Categories 3 & 4 and the S&P Financials index final difference is -1.10%. Lastly, the difference between categories 3 & 4 and the GSIBs is -2.41%.

Did Tier 3 and 4 Banks outperform either GSIB banks or the S&P Financials since the publication of the proposed rule in October 2018?

Figure 2 shows the cumulative returns for the three groups. Again, we find that Tier 3 and 4 banks underperformed GSIB banks by 2.01% over the longer period. Even allowing for the longer time period for the market to absorb the information, those banks that got regulatory relief did not see better returns.

This analysis, of course, does not control for many other changes that occurred during this period and the longer the period, the more likely that multiple other factors interfere with a clean interpretation. For example, while GSIB banks did not get regulatory relief, the Federal Reserve released the results of their stress tests in June 2019 that showed all banks passed and were allowed to pay dividends. This and other broader developments may have been more beneficial to the GSIB banks. Another alternative that is possible, but not likely, is that the market viewed these changes as an unwelcome loosening of important components contributing to the long-term return prospects for these banks. Nonetheless, if viewed as regulatory relief tailored to midsized banks, and if it had been significant enough, we would have expected to see it in the data, and we did not.

The cumulative returns for the three groups. The portfolios are cap-weighted. The first black line is the date of the proposed tailoring rule announcement and the second black line is the date of the final tailoring rule announcement. The final difference between the GSIBs and the S&P Financials index is -2.01%. Categories 3 & 4 and the S&P Financials index final difference is -.86%. Lastly, the difference between categories 3 & 4 and the GSIBs is 1.15%.

Conclusion:

Our analysis suggests that the market does not expect the recent revisions in bank regulatory standards to have a material effect on bank profitability. The market may have already incorporated a deregulatory premium earlier than October 2018. However, a general sense that there was going to be regulatory relief that formed after the 2016 election would likely have affected all banks. That we did not find any excess returns for the midsized banks suggests either that the regulations were not particularly relevant for returns in the first place or that the relief was rather modest. More likely, other factors have had a larger impact on relative bank returns, but in any case, more analysis and research on the cost and benefits of bank liquidity and capital regulations are needed. The Golub Center for Finance and Policy will continue to focus on these issues related to bank regulation and systemic risk.