Climate Change

4 ways the US election could impact 2025 climate policy

A Republican sweep could reverse the Biden administration’s signature 2022 climate law. MIT Sloan economist Catherine Wolfram analyzes four potential outcomes.

The 2024 U.S. election is a pivotal moment for climate policy in the country, heightened by the expiration next year of a key piece of tax legislation.

The U.S. is already behind schedule on its Paris Agreement commitment to decarbonization, and that gap could widen or narrow, depending on election results and what climate policy changes are enacted or repealed.

A paper co-authored by MIT Sloan economist the former deputy assistant secretary for climate and energy economics in the Biden administration, explores various scenarios that might emerge from the expiration the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, first passed by the Trump administration in 2017.

Both Republicans and Democrats have expressed interest in extending some of the TCJA tax cuts. But extending them could raise the budget deficit, unless Congress finds a way to pay for them.

This is where climate policy may come into play, Wolfram said, given that the U.S. historically has enacted climate policy through the tax code.

Will Republicans dismantle the Biden administration’s landmark climate investment bill, 2022’s Inflation Reduction Act? Will Democrats expand the law if they win the House, Senate, and presidency?

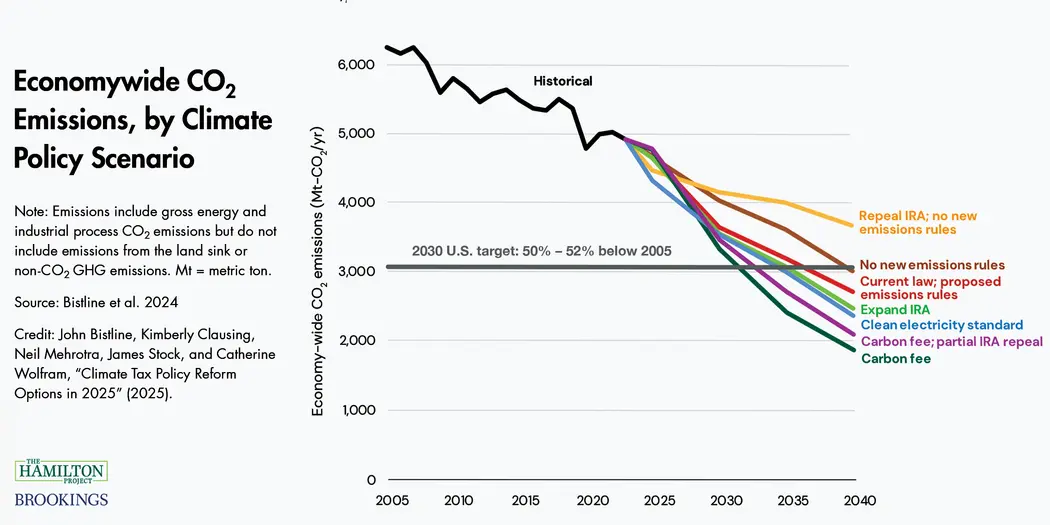

Published by The Hamilton Project, “Climate Tax Policy Reform Options in 2025” tackles those questions by looking at seven scenarios and evaluating their likely fiscal impact and effectiveness at cutting emissions with regard to the U.S.’s 2030 emissions reduction targets.

In an interview, Wolfram highlighted the four scenarios she believes are most likely to play out, depending on November’s election outcomes.

1. Repeal the IRA and add no new emissions rules

A Republican sweep could lead to a repeal of both the climate provisions included in the Inflation Reduction Act and regulatory proposals for power plants and vehicles, Wolfram said, acknowledging that Republicans have been “hard to pin down” on what they intend to do.

“If there’s a Republican sweep, it might make it attractive to end the Biden administration’s signature climate bill and try to help pay for some of the general tax cuts by ending the tax credits for clean technologies,” she said.

However, a lot of the investments subsidized by the IRA are in red congressional districts and red states, such as Texas and Iowa, in addition to swing states like Michigan.

“That’s where a lot of the wind [investment] is popping up,” Wolfram said. “So I think there’s this tension between, do you want to ‘own the libs’ and get rid of their signature piece of legislation, or do you want to represent your constituents’ economic interests?”

2. Maintain the current law and add no new emissions rules

Wolfram said there’s a chance that nothing major would change regarding policy. She noted that the climate discussion has taken a backseat to other election topics, such as immigration and reproductive rights. At the Democratic convention, for instance, climate barely received a mention.

“My sense is that climate is in the top 15 issues for voters, not the top five,” Wolfram said. “I think people see that the climate is changing, and there are wildfires, bigger storms, and other tells, but it’s definitely not in the top five issues that voters care about.”

3. Add a carbon fee

Typically, progress toward decarbonization occurs in two ways: by subsidizing investments in clean energy and by making companies pay for being dirty with a carbon fee, Wolfram said.

Related Articles

Up until now, the U.S. has resisted carbon fees, though a growing number of economists, Wolfram included, believe countries will not be able to reach their Paris Agreement pledges without a carbon tax. “You need to have a price on the dirty stuff,” said Wolfram, who has written extensively on the merits of a carbon pricing. “That’s what seems to work around the world.”

While Wolfram’s research shows that the emissions reductions of the IRA are “significantly augmented” under scenarios that add a modest carbon fee, neither party has fully embraced fees so far, even though the U.S. has excise taxes on coal and oil already.

What’s more, companies will encounter a carbon fee when exporting abroad, Wolfram said. “A lot of other countries are implementing carbon pricing, and they’re starting to do border adjustments so that if U.S. companies are trying to export, they will face a carbon price at the border,” she said. “They’re just sending the check to Brussels or London, so I think that’s another dynamic that’s giving this some urgency.”

4. Partially repeal the IRA and add a carbon fee

Wolfram’s “economist dream scenario” involves a partial repeal of the IRA to remove the low-hanging fruit, such as electric vehicle credits — which are “quite expensive,” and some people are willing to buy an EV without them — and the implementation of a carbon fee.

“One of the concerns is that if you make energy more expensive through a carbon tax, consumers are going to be left paying a higher bill. But if, through the IRA, you’ve given them access to alternatives, like heat pumps or electric vehicles, then they have more options” for keeping energy costs low, she said.

Wolfram sees this scenario as being possible in the event of a divided Congress — for instance, if the Republicans take the Senate and the Democrats take the House with a Harris administration.

“You could imagine coming up with some kind of grand bargain where the Republicans get the political victory of a repeal and the Democrats get to preserve the pet parts of the IRA,” she said. “If you then add the carbon fee, you raise a lot of money and you can keep the environmentalists happy because you keep the emissions on a downward trajectory.”

“Climate Tax Policy Reform Options in 2025” was co-authored by John Bistline, Kimberly Clausing, Neil Mehrotra, and James Stock.