Organizational Culture

Agile at scale, explained

Taking agile to scale is major departure from the traditional command-and-control style — and it’s becoming increasingly popular. But you can’t do this halfway. Here’s what to know before you dive in.

With talk of scrums and sprinting, corporate environments are starting to sound a bit more like rugby matches these days. But the terminology, borrowed from the popular English sport, actually refers to an alternative way of managing work: agile.

Kristine Dery, a research scientist with the MIT Center for Information Systems Research who is studying agile at scale, also known as agile management or scaled agile, as it relates to the employee experience, said making the switch represents a major overhaul for any organization.

But, by many measures, it appears to be a more effective way of working in a rapidly-evolving digital environment. Large companies like Spotify, Ericsson, Microsoft, and Riot Games have all adopted the method.

So what is agile, and is it the right fit for your firm? And what should you do to prepare for implementing it?

What is agile?

Agile, first introduced in 2001 in the Manifesto for Agile Software Development, started out as a method used in software development that challenged the traditional, linear “waterfall” development model, in which entire projects are pre-planned, then fully built out before they are tested. Agile’s approach offers iterative flexibility, with small parts of projects being built and tested simultaneously.

Taking a more iterative approach makes it easier to keep projects aligned, on track and relevant, and it allows for the release of “minimum viable products” to gather more frequent user feedback from clients earlier in the process. That helps guide the team on what needs to be changed or altered to make the product more successful.

“The traditional method of managing, the waterfall method, which is very inflexible, planned-in-advance, linear, and not iterative at all, wasn’t lending itself at all to the flexibility and the adjustments that were necessary to make great software,” said Carine Simon, a senior lecturer and industry liaison at MIT Sloan, who helped lead a transition to agile at scale at Liberty Mutual Insurance. “[Agile is] iterating with customer feedback, prototypes, and tests, versus taking some requirements and issuing the product maybe a year later, when the customer’s requirements have changed or technology has evolved.”

The idea is to allow the end user to have a clearer view of their requirements for the finished product earlier in the process of creating it, instead of receiving a final product that may not end up looking exactly like what they had anticipated.

“It’s a series of experiments, as opposed to one linear project where you get to the end and find out if it works,” Dery said. “On lots of projects with long timeframes, once you get to the end, the problem has shifted and often you’ll be coming up with a solution that is now removed from the problem.”

What is agile at scale?

Seeing agile’s success in information technology and the growing prevalence of technology throughout business at large, many companies began to ask whether the method’s practices and philosophies could be scaled up to apply with equal success to other projects or even entire business functions, Simon and Dery said.

“[Companies] said ‘Let’s see if we could move projects forward, not necessarily faster, but to get better results out of some of the projects we have, given that just about every project involves technology to some extent. Maybe it’s an opportunity to work differently,’” Dery said.

Simon said companies that adopt agile at scale benefit from breaking down functional silos and pooling the talent from each function into teams. “In the traditional management, you have one leader for each function … but the coordination and collaboration between those functions is often difficult, whereas if you create one team that pools members from each, then the thinking is that the project will be more successful. All projects are going through a similar mode of management.”

During her time at Liberty Mutual, Simon said teams developing customer-facing products began adopting agile methods at scale to redesign the process for onboarding new customers. That required pulling together the various teams involved in parts of the process to bring their perspectives together: the marketing team who designed onboarding collaterals, the call center team whose agents are on the phones with the customers, the finance team who is dealing with the different payment methods.

“It brought a team together with all those perspectives, making them collaboratively work on redesigning the process iteratively to come up with minimum viable products,” Simon said.

The switch, she said, saw the team members empowered to own the product from beginning to end and led to better products.

But adopting agile at scale means more than just plugging a new tool into an existing framework. It requires a paradigm shift at the organizational level, Dery said. “The biggest downfall is not understanding what a vast departure it is, and not investing in the learning and support that’s required to build the environment that enables it to work effectively.”

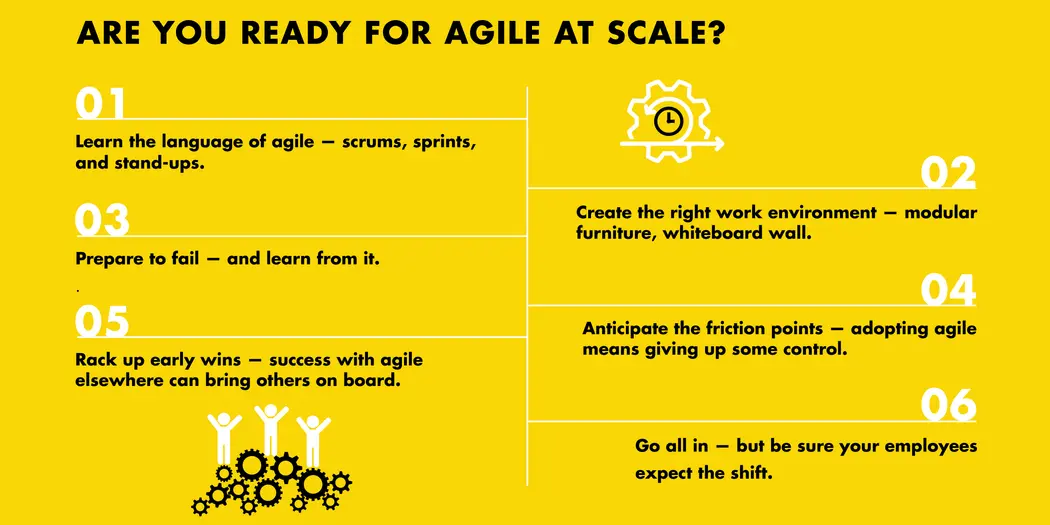

Learn a new language

Dery said those who plan on applying agile to their organization will need to learn to work within an entirely new methodology that has its own lexicon of terms to describe its workflow.

During the process, known as a “Scrum,” work is assigned to cross-functional teams and divided into “sprints” — the basic unit of progress delineated by a specific timeframe, usually two weeks to a month.

Then, there are “scrum masters” who coordinate the team’s activities, and each day members meet for short “stand-up” or “daily scrum” meetings to provide updates on the prior day’s work, the work planned ahead, and any potential stumbling blocks.

“It’s a way of coming together to make sure those things are addressed. They keep the project moving forward,” Dery said of the stand-ups. Indeed, agile sprints were so-named to evoke a sense of pace.

Development is a trial-and-error, test-and-learn process, Dery said, and the product is rolled out in small pieces at the end of each sprint. Features that still need to be completed are added to a “product backlog,” with the most crucial taking highest priority.

Within a Scrum, team members are typically afforded more autonomy in how they approach tasks and resolve problems in a departure from a command-and-control structure of project management. The concept is that those closest to the work know best how to address issues.

“You’re working on the problem all the time, as opposed to working on the solution,” Dery said. “It’s a different way of thinking and organizing, and it requires a different set of disciplines. You’re constantly assessing where you’re at, what you’re doing, and what you want to deliver.”

Ready for this? Go in fully committed.

Dery said companies that decide to deploy agile at an organizational scale often find that the difficulty in doing so is much greater than what they had anticipated, especially when it comes to the impact such a shift can have on employees.

“There’s no just ‘dipping your toes in the water,’” she said. “The experiment is going in fully committed to see how this allows you to work differently and build value.”

A traditional, static office design isn’t necessarily the best fit for an agile work environment, she said. They’re much better suited to a more flexible space, with movable furniture and design thinking walls. “You want it visual, for working out loud, to work it out where they are at,” she said.

Since the method requires significant close teamwork, organizations will need to ensure there are adequate video and telecommuting technologies in place for times when all team members can’t be in the same location.

Providing coaching for employees to change their work habits to better align with the agile management style is also crucial to success. “You need to be supporting not just their capabilities, but also helping build the type of work habits more suited to this way of working,” Dery said.

Scrum masters are usually responsible for ensuring that happens, and for attracting the right kind of talent to provide it.

Watch out for these friction points

Agile and waterfall methodologies are so different that they often end up butting heads when a project moves from one to the other, Dery said.

“They’re such very different ways of working,” she said. “If you’ve done one part in agile and then you throw it into waterfall, it’s a very, very different approach. It causes a lot of things to stall or get lost as [the project] is translated from one to the other.”

Dery said it’s still unclear what the best approach may be to head off such areas of friction as companies roll out agile to greater extents.

Simon said giving up the sort of control that agile requires can be threatening to some managers, and any company weighing a shift to the style should identify the functions or departments that lend themselves to it and implement them there first. If it’s successful, the track record of wins can help sway other functions to give it a shot.

Some functions whose processes are very certain and repeatable or governed by outside regulatory or compliance requirements may never need agile management, nor would they necessarily benefit from it, she noted. Even if agile looks great on paper, it won’t work if there’s too much resistance.

“In customer-centric processes where customer input is key, and in that sense it’s quite uncertain or fast-changing, then those would be the types of areas in a firm that lend themselves to agile,” she said. “You need some early wins, picking the top areas of your firm to try agile and get familiar with it, so that managers can get on board.”