Behavioral Economics

Car access more than tripled in value during early COVID-19

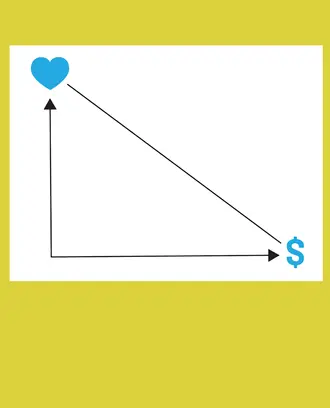

Cars are expensive but their option value is even higher, creating a major barrier to alternative urban mobility systems.

A new survey from the MIT Energy Initiative’s Mobility Systems Center finds that while cars are expensive and underused, they provide U.S. owners with a sense of security and control — feelings that contributed to the more than threefold increase in the value of car access during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to survey respondents who owned at least one car, it would take an average of $3,300 to give up ownership and use of their car for just one month during the pandemic, compared to an average of $933 during a typical month. They would need an average of $11,200 in compensation to give up their car ownership and use for a full pre-pandemic year, despite the fact that cars are parked for 95% of their lives, and households spend an average of $9,300 a year on their cars.

The results highlight the significance of option value — in this case, that the car is there for its owner at a moment’s notice to get them where they need to go. It's a concept that mobility experts and transportation planners must consider if they want to create successful Mobility-as-a- Service systems — a package of transportation options so people no longer need to rely on owning and using their individual cars.

“We can say people do value the car more than it costs,” said Joanna Moody, research program manager for the energy initiative’s Mobility Systems Center, one of the energy initiative’s low-carbon energy centers. “But until we can provide them with an alternative that rivals the private car — that gives them the convenient and certain mobility that they need, at a comfort level that they need — they are not going to switch, and that's a perfectly rational choice.”

Moody presented the findings during a recent webinar. Her co-researchers on the survey include MIT Sloan professor David Keith, Liza Farr, a graduate research assistant from the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning, and Marisa Papagelis of Wellesley College.

The survey was conducted between June 10 and July 2, with a sample size of 4,022 respondents from four cities: Washington, Chicago, Dallas, and Seattle.

The survey originally focused on several questions:

- What is the value of the personal car and how much of that value is from ownership versus use?

- If mobility options other than personal cars were widespread and high quality, how might the attractiveness of car ownership and use change?

The research team added a third question about the impact of COVID-19 based on the timing of the survey and the initial wave of the pandemic.

To measure respondents’ willingness to get money for giving up access to a particular type of transportation, the researchers posed a series of questions, each with two choices:

- Keep access to X transportation mode and receive no money.

- Give up access to X transportation mode for a year (or in the case of COVID-19, one month) and receive a randomized amount of money.

The survey-takers were asked to make these choices for three scenarios: giving up access to ride-hailing services (like a taxi, Uber, or Lyft); giving up access to their primary car; giving up access to their primary car where all of their car trips would be replaced by a “new, free, ubiquitously available ride-hailing service.”

Car owners said it would take an average of $3,300 to give up ownership and use of their vehicle for just one month during the pandemic.

According to the survey, people were more likely to give up their cars if they were: male, Hispanic, lived in one-car households in an urban ZIP code, used their cars less for their day-to-day travel, or were offered carpool programs or subsidized transit by their employers.

While the value of car ownership increased during the pandemic, the value of access to ride-hailing services didn’t change very much. Survey respondents said that they would only need about $10 to give up access to ride-hailing for a month — in both pandemic and pre-pandemic times.

Moody said the tripling in how much people value cars during the pandemic is a result of living in an uncertain time, where we might not trust other transportation alternatives, or we might need transportation at the drop of a hat.

“There is a security, a sense of ownership, and control having your own vehicle — that provides a lot of value to individuals,” Moody said. “Just the fact that if I needed to get somewhere in a hurry, that car is there for me, and I don't need to worry about it. I just jump in and it takes me where I need to go.”

‘Building the value of alternatives’

While there might not be any immediate short-term things that can be done to rival the value of private U.S. car ownership and use, Moody said services and infrastructure improvements that support public transit, walking, and biking could help get people out of their cars in the medium-term. In the longer term, land-use planning that encourages dense, mixed-use, transit-oriented development could decrease dependence on personal vehicles.

Related Articles

Moody said she and her fellow researchers and mobility experts must continue to examine what makes people value their private cars, because this can inform the design of Mobility-as-a-Service packages. This means focusing on how to strengthen the case for urban mobility systems — like connecting public transit with environment impacts, public health, and social inclusion — rather than criticizing people’s choice for using cars.

“We need to be thinking about building the value of alternatives, not trying to call people irrational for valuing the car as it is now,” Moody said. “Because we've built urban environments and transportation systems that makes the car the rational choice for most U.S. residents.”