Credit: Fahroni / iStock

After decades of failed attempts at climate legislation, the U.S. just enacted the largest climate policy legislation in its history: a $370 billion bill designed to reduce reliance on fossil fuels and spur investment in renewable energy.

“The Inflation Reduction Act is a solid step on our journey to zero emissions, but a lot of work remains to be done,” said John Sterman, a professor at MIT Sloan and faculty director of the MIT Climate Pathways Project.

To avoid the worst harm from climate change, global greenhouse gas emissions must fall by nearly half by 2030 and then drop to net zero by midcentury, according to the United Nations Climate Action initiative. Hundreds of organizations and countries have jumped on the net zero bandwagon: Apple 2030. Amazon 2040. US 2050. China 2060. That’s good news, Sterman said in an interview, but because the goals are net zero and not just plain zero, they allow or even require carbon offsets.

Offset logic goes like this: If it is cheaper for a company to buy an offset that cuts emissions somewhere else instead of in their own operations, then offsets are cost effective. However, many of the offsets being sold today are based on dubious assumptions and can make climate change worse, Sterman said. In a recent op-ed in MarketWatch, he described a simple framework that companies and consumers can use to ensure that any offset they buy actually cuts emissions.

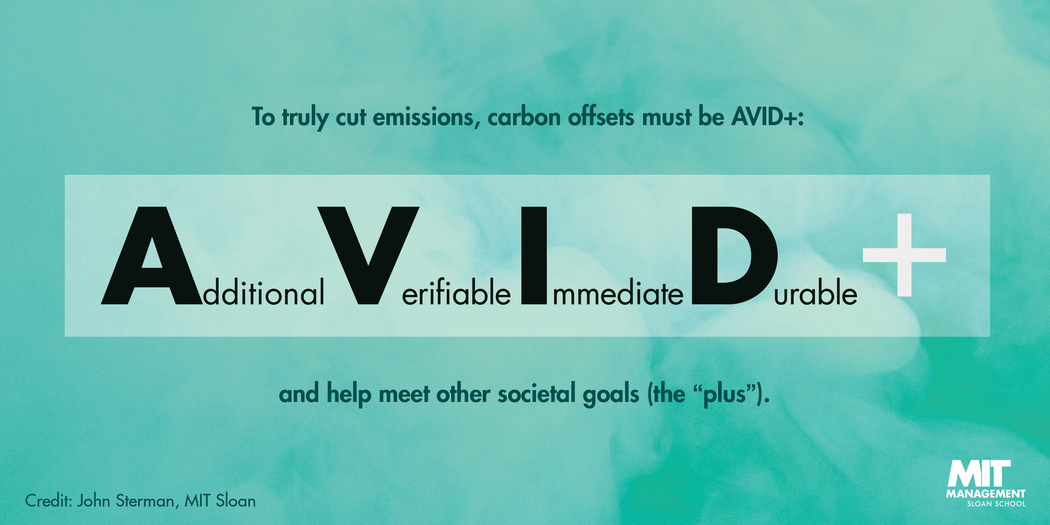

Sterman calls his framework AVID+. To truly offset their emissions, companies must ensure any offsets they buy are Additional, Verifiable, Immediate, and Durable — and, if all four of these requirements are met, then firms should favor offsets that also help meet other societal goals such as creating good jobs, improving health, and fostering social justice (the “plus” of AVID+). Here are details.

- Additional: Offsets must reduce emissions that would not otherwise be cut. Saving part of a forest, for example, isn’t additional if other trees are cut down instead, nor is using a Power Purchase Agreement to invest in a solar farm that’s already permitted and produces power cheaper than a nearby coal plant. Because it has such low costs and risk, the farm’s capacity would likely be sold to other parties, so the investment doesn’t reduce emissions below what they would be without your action.

- Verifiable: You must be able to verify that emissions actually fall. If you’re going to plant trees, you have to verify that they were actually planted and that they will survive for decades to come. If you fund efficient, low-emission cook stoves for the rural poor in the developing world, you have to verify that they are actually delivered, kept in working condition, and used.

- Immediate: Every company and investor knows the time value of money: A dollar today is worth more than a dollar in 2050 because of the interest you can earn. In the same way, there’s a time value of carbon: Your flight today dumps carbon dioxide into the atmosphere right now, worsening climate change from this day forth. Saplings planted today won’t grow large enough to offset today’s emissions for decades, nor will investments in speculative technologies like nuclear fusion or direct air capture, even if they eventually become viable.

- Durable: Carbon dioxide emissions stay in the atmosphere for a century or more, so you must offset an equivalent amount of emissions for at least that long. Trees planted today are more likely to succumb to wildfire, disease, pests, or extreme weather as the world warms, and do not provide durable carbon storage.

- + (Plus): Offsets should multisolve — they should advance other goals such as job creation, poverty reduction, health care, and social justice, in addition to their climate benefits.

The AVID+ criteria are simple, but satisfying them is not easy. All four must be met. Fail on any one, and a proposed offset won’t actually reduce emissions much, if at all, Sterman said. Buying offsets that fail the AVID+ test wastes resources you could use to actually cut your emissions, making climate change worse. And buying offsets that aren’t AVID+ exposes you to well-justified accusations of greenwashing, risking your reputation and potentially alienating customers, communities, and capital markets.

Recognizing that there aren’t perfect offsets, what might qualify? Deep energy retrofits and rooftop solar for low-income housing can be AVID+:

“Few low-income households can finance the work themselves, and since most renters pay their utility bills, their landlords lack the incentive,” Sterman said. “Such retrofits are therefore additional. The energy savings are verifiable from utility bills. Projects take about a year, so emissions reductions are nearly immediate. Good retrofits can significantly extend building life, so benefits are durable. Plus, retrofits create jobs, reduce energy bills, and improve health.”

Startups BlocPower and Midday Tech are good examples, he said.

Of course, planting trees, funding efficient cook stoves, and similar actions can generate other benefits, and some companies and individuals may choose to invest in them. But if an action fails any of the AVID criteria, you cannot legitimately claim that these investments offset your own emissions, according to Sterman.

Some companies are stepping up to the challenge. Walmart, for example, is the first U.S. retailer to make a zero emissions commitment that does not rely on carbon offsets, though its pledge does not (yet) apply to their supply chain, he said.

“The best way to reach net zero is still just to reach zero: Cutting emissions in the first place,” Sterman said.

Read more: MIT Sloan research on sustainable business