Research

Lost Einsteins: The US may have missed out on millions of inventors

Innovation has slowed in the U.S., stymying economic growth. To get back on track, the U.S. needs more low-income children, women, and minorities to become inventors — but that won’t be easy.

Innovation fueled economic growth in America for the past century, but since the 1970s, innovation (as measured by fundamental productivity growth) appears to have slowed [PDF] — from an annual increase of 1.9 percent to 0.7 percent — and so has economic growth.

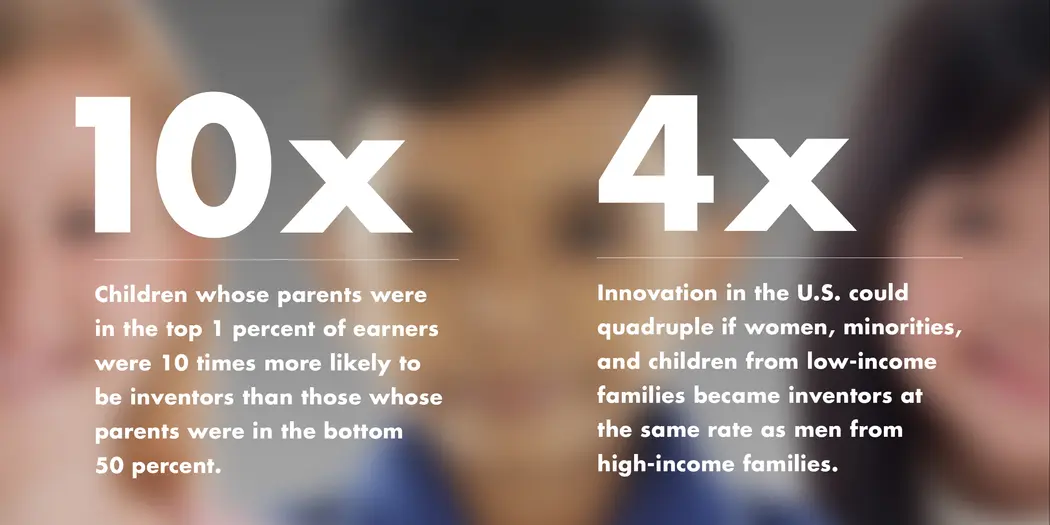

A new study shows that, thanks to inequality, the U.S. has potentially missed out on millions of inventors during that time — what the researchers refer to as “lost Einsteins.” Kids born into the richest 1 percent of society are 10 times more likely to be inventors than those born into the bottom 50 percent — and “this is having a big effect on innovation,” MIT Sloan professor John Van Reenen said.

The research also shows that innovation in the U.S. could quadruple if women, minorities, and children from low-income families became inventors at the same rate as men from high-income families. Making that happen is the hard part, though. It means exposing more children to innovation when they are young — and the younger they are, the better.

The wealth factor.

Since innovation is largely seen as a means for economic growth, researchers at the Equality of Opportunity Project wanted to see what part childhood wealth plays on future innovation.The research [PDF], completed by Van Reenen alongside Raj Chetty, Xavier Jaravel, Neviana Petkova, and Alex Bell, showed stark results.

“The most striking thing was how sharp the relationship was between the wealth of your parents and whether you grew up to be an inventor or not,” John Van Reenen said.

By linking patent records with de-identified IRS data and school district records for more than one million inventors, the researchers found that, while ability does play some part in a child’s chance of becoming an inventor in the future, it is far from the biggest factor.

Instead, wealth played a much larger role. Among children who excelled in math in third grade, those whose families’ incomes fell into the highest fifth of the population were more than five times as likely to be inventors than those whose families’ incomes were in the lowest fifth.

This disparity is amplified among children whose parents were in the top 1 percent of earners — they were 10 times more likely to be inventors than those in the bottom 50 percent.

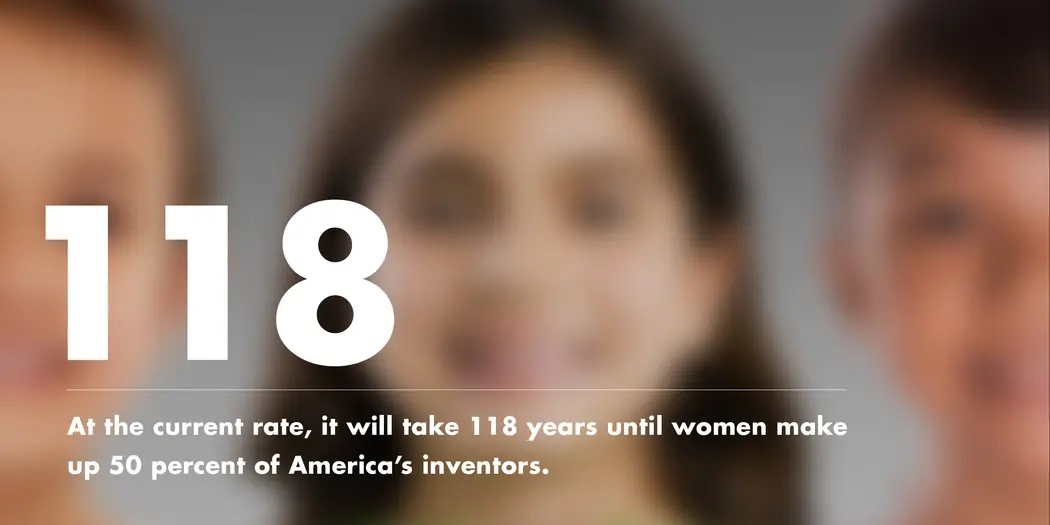

Broken out by race, white children were three times as likely as black children to be inventors. Only 18 percent of inventors were women.

But why?

You cannot be what you cannot see.

Researchers have long known that innovation is more concentrated in certain regions — near large universities, research centers, and areas with a high concentration of businesses. But nobody has previously asked how that affects children growing up in those areas.

The researchers found that growing up in one of these clusters of innovation makes kids more likely to be inventors themselves — likely because those children are being exposed to innovation at an early age.

“Your community, your family, your friends — all these things seem to matter,” Van Reenen said. And for a very simple reason — if kids grow up around innovation, they grow up hearing people talk about innovation, and begin thinking they can be inventors.

And it is industry specific. If a child’s parent in an inventor in synthetic rubber, that child is more likely to grow up and invent something in the synthetic rubber field. “There isn’t a specific gene for that — more likely it is due to something people call ‘dinner table capital.’ You are sitting around, talking about things, and you pick that up from your parents,” Van Reenen said.

What’s more, girls who are exposed to female inventors are more likely to grow up to be inventors themselves — the same is true for boys. “While having inventor exposure is always good, it is particularly strong when you see someone of your same gender,” Van Reenen said. While the researchers were unable to break this same metric out based on race, Van Reenen thinks that as research gets more granular, this is likely to be true for minorities, as well.

Increasing exposure.

Current U.S. policies meant to increase innovation aren’t working. The researchers found that things like tax incentives only affect those lucky enough to have already been exposed to innovation, and people who are inventors would likely be so even if the tax incentives didn’t exist.Instead, children need to be exposed to innovation from an early age.

The researchers propose a number of ways to do that — everything from mentoring programs and internships to school programing and interventions through social networks. The goal is to get women and minorities to connect with people like them who have become inventors, to show them that they can be inventors, too.

Whatever policies are eventually adopted, policymakers need to think in terms of long-term solutions. “You want is to increase the pipeline of people on the supply side who are great inventors,” Van Reenen said. “You want to take the talent that is already in America and get those kids imagining themselves being an inventor or potential inventor. It is not a quick fix, but in the long run it is going to be a more effective policy.”

And the younger children are reached, the better. The researchers looked at third grade math scores, but by that point the effects of inequality are already starting to take hold.

The ability to be an innovator doesn’t vary across race, gender, or income groups — but circumstances do. Many of the children in the under-represented groups could have grown up to be inventors, but didn’t, leaving us with a generation of “lost Einsteins.”

“These people have the talent to be inventors, but they don’t imagine that they could be,” Van Reenen said. “We are losing out in a real source of knowledge and ultimately growth — a factor that we need.”