Behavioral Science

Managers' prior work evaluations can affect diversity efforts

For a fairer and more diverse way of hiring and promoting, managers must be clear, specific, and in agreement about what they look for when awarding merit.

Spurred by calls for a more diverse workforce, companies are striving to remove bias from their hiring and recruitment processes and their performance evaluations.

But new research from MIT Sloan professor cautions that efforts to standardize hiring and promotion metrics may be undercut by managers’ evaluation experiences as employees.

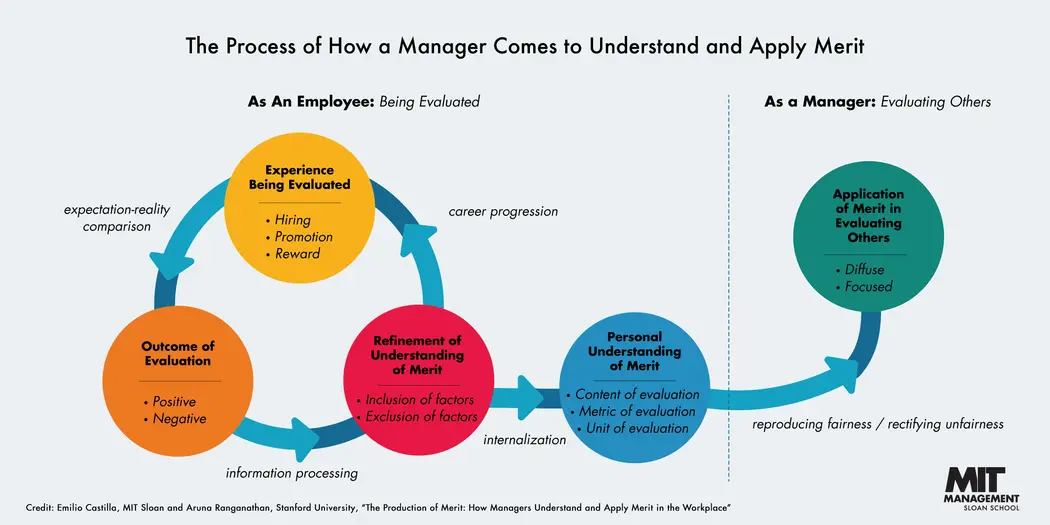

In their article “The Production of Merit: How Managers Understand and Apply Merit in the Workplace,” Castilla and co-author Aruna Ranganathan of Stanford University show that a manager’s prior career experience can become a “blueprint” for how they assess and apply merit. Since no two managers’ careers are exactly alike, that leaves a lot of room for interpretation in an area that advocates say needs more transparency and equality.

“When these managers start making decisions on behalf of your organization, they bring these antecedents, they bring prior experiences as employees or as managers in other organizations,” Castilla said. “This shapes their own approaches to evaluating merit and talent, and therefore, may potentially undermine diversity efforts because companies will be hiring using different standards depending on who is doing the recruiting and selection.”

Here's a closer look at the research, as well as insight into how managers can standardize their assessment of merit.

Diffuse and focused approaches

The researchers interviewed 41 MBA students from an American business school and 11 managers of a large Silicon Valley tech company (anonymized as Bay Area Corp.), and studied 56 anonymous online reviews written by Bay Area Corp. managers about employment-related decision-making at the company.

The researchers asked the MBAs and managers about their previous job roles and the cultures and structures of their prior workplaces. They also asked about their current organizations’ hiring practices and core values, and the routines they encountered at work and how they perceived them.

The researchers took a conversational approach to asking questions and allowed the interview to evolve with the person’s responses. In an effort to gather “preconceived interpretations of merit, rather than invoking definitions used in corporate discourse,” the researchers did not use the word “merit” until the interviewee said it or until later in the discussion, they write.

The MBA students came from a variety of professional and personal backgrounds. About two-thirds of the Bay Area Corp. managers were male, white, had an average age of 32, and had about three years of managerial experience. There was limited demographic data on the anonymous online reviews from Bay Area Corp. managers.

The researchers transcribed the interviews and studied the words and phrases that explicitly mentioned merit and the words and phrases that shaped the way a person understood merit. They coded those words and phrases, and by analyzing them, the researchers learned that managers tended to determine merit in one of two ways:

- A diffuse approach considers an employee as both an individual and as a team member. The employee’s work actions and personal qualities are considered on a quantitative and qualitative level. This is a way of evaluating merit in a multifaceted way.

- A focused approach considers an employee on an individual level and quantitatively evaluates their work. This is a narrower way of evaluating merit.

Managers who had mostly positive evaluation outcomes in their careers tended to take a diffuse approach to applying merit, and included actions and traits they associated with those positive experiences into their consideration. For example, a white male manager interviewed for the study said he was offered a job because of his “connections and likeability,” and now when he hires and promotes, he considers someone who understands both numbers and “feelings.”

Managers who experienced mostly negative outcomes as employees tended to be narrower and more focused in their approach to merit, “to rectify what they thought was unfair as criteria that was incorporated in the process of their being evaluated,” Castilla said.

For example, an Asian American woman told the researchers she had a previous negative promotion experience due to her “gentle nature” and not being outspoken enough. In turn, she excluded “assertiveness” as a factor when assessing employees’ merit.

Women and nonwhite professionals in the study reported experiencing relatively more negative evaluation experiences than their white male peers, the researchers write. They were also more likely to adopt a focused approached compared with white men. The number of observations was small, Castilla said, but the pattern was “quite stark.”

“To run a workplace that is more inclusive and diverse, leaders must understand that managers in certain demographic groups may have very different approaches to merit application because of their past evaluation experiences as employees,” Castilla said.

A consensus on merit

Prior career experiences can’t be erased, but organizations and their managers can take action to standardize how they assess and apply merit.

The first step, Castilla said, is acknowledging and understanding that managers may have very different evaluation experiences based on things like race, gender, and other personal and contextual factors like being an extrovert or introvert and being exposed to different organizational cultures and structures.

Related Articles

As a result, managers will take a particular approach — diffuse or focused — to understanding and applying merit when evaluating their current employees.

While the study design doesn’t allow the researchers to empirically determine whether one approach or the other is better for merit application, Castilla said there may be particular contexts or jobs in which either might be more relevant.

Castilla said he also suspected that the two approaches may have noticeably different career implications for the employees being evaluated. He cautioned that the approaches may potentially undermine employer efforts to improve equity, diversity, and inclusion depending on the type of organization.

At the very least, being aware of these two approaches should prompt managers to stop and consider whether they’ve been clear about “the precise factors that are important to make my group or my team or my organization successful — and if so, what are those factors,” Castilla said. “Is there agreement that those factors are relevant for the position, and are they understood and applied consistently and fairly in all employee decisions regardless of their demographic and personal characteristics?”

Castilla said executives and managers should not be reluctant to have a conversation on what they want to include in their merit application. A list of concrete standards will allow for a “much fairer and [more] diverse way of deciding and implementing practices that have to do with rewarding and advancement of employees based on their talents,” he said.

“There will be more consensus on what merit and talent actually mean, and everyone will have a clearer and more consistent way of approaching all these particular key selections, promotions, and rewarding processes, to give more possibilities to individuals of different demographics,” Castilla said.

Read next: Women are less likely than men to be promoted. Here’s one reason why