“In 2006, Robert and Julia Tanner borrowed $30,000 to put an enclosed patio on their home that they had somehow managed to live without for 25 years. Why don’t you ask them about that when they’re spitting in your face while you walk them to the curb? Why don’t you ask the bank what the hell they were thinking giving these people an adjustable rate mortgage? And then you can go to the government and ask them why they listed every other regulation … You, Tanners, the banks, Washington, every other homeowner and investor from here to China turned my life into evictions.”

So Florida businessman Rick Carver lectures a young protégé in “99 Homes,” a 2014 film that casts the late-2000s housing collapse as a morality play. Carver, loaded with unforgiving moral certitude by the actor Michael Shannon, orders the Tanners’ eviction while standing in an empty McMansion. He’s living there part time after evicting the tenants when their mortgage went underwater.

“99 Homes” is littered with ruin. Nobody — the poor, the Tanners, the McMansion dwellers — escapes, or escapes blame for, the crisis. Now research from MIT Sloan finance professor Antoinette Schoar finds this picture more true than is commonly accepted. In fact, Schoar argues, it was middle-class borrowers with good credit who drove the largest number of dollars in default.

“A lot of the narrative of the financial crisis has been that this [loan] origination process was broken and therefore a lot of marginal and unsustainable borrowers got access to funding,” Schoar said in September at the MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy’s annual conference. “In our opinion, the facts don't line up with this narrative … Calling this crisis a subprime crisis is a misnomer. In fact, it was a prime crisis.”

That’s important to know, Schoar said, because a new narrative of the crisis could inform public policy decisions and help prevent a repeat event, or at least soften the blow.

“For this, better screening at origination alone doesn’t do the trick,” she said. “We need macroprudential tools to actually protect ourselves against these types of dynamics in the housing market.”

In a paper forthcoming in The Review of Financial Studies titled “Loan Originations and Defaults in the Mortgage Crisis: The Role of the Middle Class,” Schoar and her co-authors (MIT Sloan PhD graduates Manuel Adelino and Felipe Severino, now professors at Duke University and Dartmouth College, respectively) show that in the run-up to the housing collapse, both credit and defaults expanded proportionally across borrowers of every income level and every credit rating. And yet when the bottom fell out, the researchers found, there was a sharp increase in delinquencies for middle-class borrowers and borrowers with “prime” — or high — credit ratings.

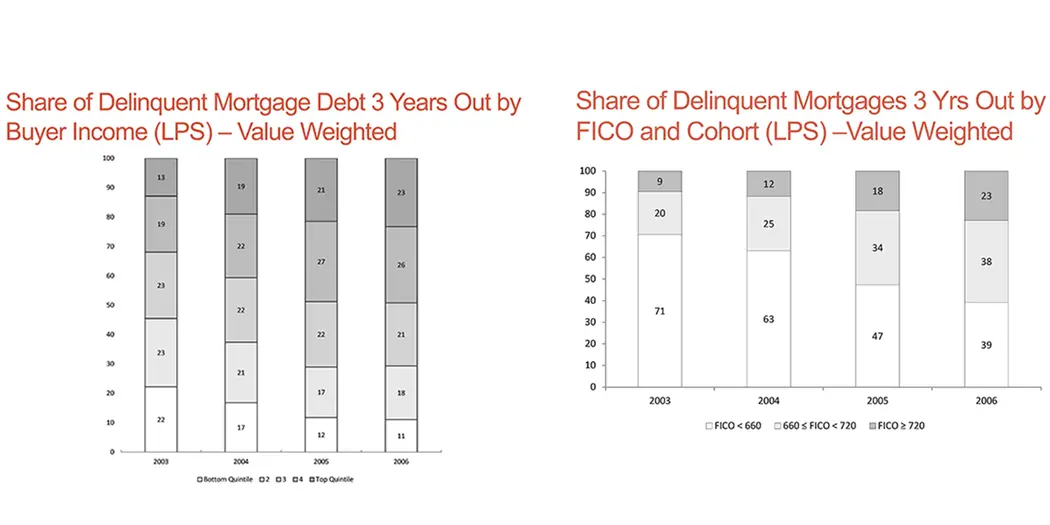

While all types of people participated in the crisis, borrowers defaulting on bigger mortgages were responsible for a greater dollar amount in defaults. The researchers found that the top quintile of borrowers by income were responsible for 13 percent of delinquent mortgage debt in 2003. That share increased to 23 percent by 2006. Meanwhile, the bottom quintile of borrowers saw their share of delinquent mortgaged debt drop from 22 percent in 2003 to 11 percent in 2006. The shift in the middle was less pronounced, but tells the same story. And the researchers found a similar shift in the share of delinquent mortgage dollars when segmenting borrowers by credit score.

Everyone bought in

So what really happened? Schoar and her co-authors believe there was an increase in leverage among borrowers of all income levels. Homeowners and investors bought and sold homes at an increasing speed between 2000 and 2006. House flipping was especially pronounced in areas of the country that saw high housing price growth between 2002 and 2006. This is when the Tanners put in their enclosed patio.

“Given that it's such a systemic event across income groups and especially in the middle class, it points to the fact that households as well as banks really believed in this house price appreciation and thought that it was sustainable,” Schoar said in an interview. “And they acted on this feeling that they were richer because their home was worth more. Once the economy slows down, then it becomes tougher for people to pay their mortgages, but also they have less incentive to pay them if the house is underwater. It points to the fact that this was a house price bubble that you could say most people in the economy seem to have bought into.”

When the economy slowed, defaults went up across income spectrums. But while the chance of a low-income borrower defaulting increased from 6 percent pre-crisis to 12 percent post-crisis, the chance of a high-income borrower defaulting went from almost zero to around 5 or 6 percent. And the latter group was defaulting on bigger loans.

Prevention, planning, and regulation

The first version of Schoar’s paper was released in 2015, when conventional wisdom among economists and in the popular press said the housing crisis was caused by a shift in debt to low-income households through subprime mortgages.

Professor Antoinette Schoar at the MIT Golub Center for Finance and Policy annual conference

“She and her co-authors really opened this up. Once you saw what she had shown, then it raised all kind of other questions that went much deeper into what had happened,” said Paul Willen, a senior economist and policy advisor at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. Schoar’s paper has launched a reassessment of the housing crisis among economists and researchers, Willen said. In research presented last summer at the National Bureau of Economic Research, Willen shows that the share of debt remained stable between high-income and low-income borrowers leading up to, during, and after the housing crisis.

“I think everybody is now going back and revisiting all these questions. There are new facts that any theory of the financial crisis has to match,” Willen said.

Both Schoar and Willen said preventing another housing bubble could be futile (a 2015 book chapter by Willen states bluntly that “… economists should acknowledge the limits of their understanding …”) and that instead policymakers should focus on ensuring that a decline in house prices will not shatter the banking industry as it did in 2008.

“From a policy perspective, what that means is that we need to understand and be prepared to absorb these types of losses when they happen or if they happen,” Schoar said. “And the question is how to absorb them. Because one way to absorb them is by saying 'Even before prices become very high, can we dynamically regulate banks so that loan-to-value ratios have to be lower when prices are high. So there's more buffer in the loans of each individual person.”

A bank collapse could also be prevented by increasing the burden on creditors in the event of failure, Schoar said. One example, she said, might be providing safeguards such as contingent convertible bonds (known as CoCos) that would convert to equity in the event of impending bank failure, stabilizing a bank before bankruptcy can occur. CoCos are undergoing a test in the European markets, where volatility among banks is causing investor concern.

While working on their paper, the researchers spoke with experts and leaders in the financial industry who, Schoar said, were skeptical of the most prominent, and more narrow, narrative of the housing crisis — that low-income, low-credit-score borrowers had been given bad loans they couldn’t afford.

“A lot of them told us they very much agreed with us and they were quite frustrated that the story hadn't been captured,” Schoar said. “Maybe by people who were very well-meaning and who wanted to point out the plight of subprime borrowers, which is definitely a big problem. It's one of many of the groups that were affected, but it became the only narrative.”