Summary: Climate and energy entrepreneurs face unique challenges — long timelines, high capital needs, and the imperative to have a positive impact on people, planet, and profit. A new book adapts MIT’s foundational entrepreneurship framework specifically for this sector.

When Bill Aulet published “Disciplined Entrepreneurship: 24 Steps to a Successful Startup” in 2013, he brought a foundational MIT entrepreneurship framework into the world for any founder to use.

But a climate or energy entrepreneur isn’t just any founder. In teaching MIT’s Climate and Energy Ventures course (formerly Energy Ventures), Aulet, a professor of the practice and the managing director of the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship, and other, later instructors found that the standard Disciplined Entrepreneurship framework didn’t fit so snugly in that sector.

So they built a new one. Written by MIT entrepreneur in residence Ben Soltoff with Aulet, Tod Hynes, Francis O’Sullivan, and Libby Wayman, “Disciplined Entrepreneurship for Climate and Energy Ventures” adapts Aulet’s original framework with climate and energy entrepreneurs in mind. In the excerpt below, the authors explain why they wrote the book.

Why is it so tough to be a climate and energy entrepreneur?

Climate and energy ventures tend to be resource-intensive, tech-heavy, infrastructure-building businesses deeply intertwined with government and large corporations. They face excruciatingly long pathways to market and must build up a sophisticated capital stack, often to produce a commodity that’s chemically or physically identical to incumbent products. On top of that, the founders bear the moral and emotional burden of dealing with the planet itself as a stakeholder — the weight of the world is on their shoulders.

Due to the long timelines and high capital needs, climate and energy ventures have what we call a high price of poker relative to other ventures. It costs more to play the game, which means that you need to make each move more thoughtfully and intentionally, including the decision of whether to play at all. The price of poker escalates over time. The longer you play, the pricier it gets, and if you cannot ante up for the next round, you fold.

Another way to think about the difficulty of climate and energy ventures is what’s called the valley of death, which is the phenomenon where promising solutions fail to reach scale due to the challenges of funding, scaling, and deploying new technology. In practice, climate and energy ventures usually face multiple valleys of death, because each stage of technology development and commercialization requires a step change in the amount of time, money, and customer traction necessary to proceed. Each stage also involves different management skills and a different set of expectations from new funders and supporters.

Valleys of death are not unique to climate and energy. They exist across all deep tech, a term for ventures that aim to commercialize complex science or engineering innovations, usually requiring substantial research and development as well as large amounts of money.

What’s different about being a climate and energy entrepreneur?

As we were writing “Disciplined Entrepreneurship for Climate and Energy Ventures,” a few people asked us why climate and energy ventures would require their own book when there are so many great entrepreneurship books already out there, including the previous books in the Disciplined Entrepreneurship series. Those volumes contain a trove of broadly applicable lessons and frameworks that can apply to entrepreneurs tackling the dual challenge of climate and energy.

However, when we spoke to the climate and energy entrepreneurs in our network, especially alumni of the MIT Climate and Energy Ventures course, they told us that the existing resources were useful, but they needed to pick and choose the relevant points, filtering carefully to figure out what was useful to them and what was not. They were not getting all the information they needed from the existing literature, and when we explored why, we could not find a single how-to book on entrepreneurship specifically for climate and energy ventures.

Disciplined Entrepreneurship for Climate and Energy Ventures

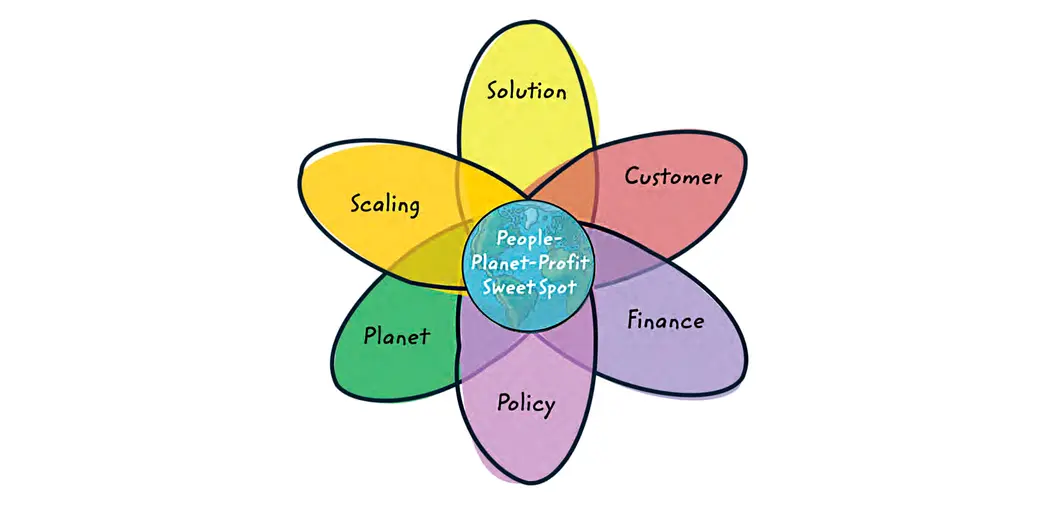

Finding the people-planet-profit sweet spot

The original Disciplined Entrepreneurship process helps entrepreneurs build a solution at the intersection of what the customer needs and what product they can develop to meet those needs (product-market fit). It also deals with the challenges of finding the right pathways and channels to reach scale (channel-market fit), and it lays some of the groundwork for building a financially successful venture. If we were to draw out these elements as a Venn diagram, it would look something like this:

Climate and energy ventures need to find product-market and channel-market fit, but they also need to account for other factors that have been simplified in the original framework. They need a robust financial strategy to fund their ventures from multiple sources over a long time frame. They need to navigate the landscape of policy and geopolitics. They often need to figure out how to build solutions at a massive industrial scale. And they need to measure planetary impact in addition to customer value. As a result, the Venn diagram for climate and energy ventures looks more like this:

At the center of the Venn diagram is the sweet spot where a venture has a positive impact in terms of people, planet, and profits. This is sometimes known as the triple bottom line.

Because of the high price of poker in this game, climate and energy entrepreneurs also need to be particularly intentional about selecting which problem to solve in the first place. They need to understand the climate landscape and the dynamics of the energy industry, as well as their own personal skills and interests, in order to find a high-value problem or opportunity. You might be spending at least 10 years of your life on this new company, so take the time up front to find the right problem to work on. You might have noticed that the Venn diagram looks a bit like a flower. We can think of problem exploration as the fertile soil from which the flower grows.

Adding problem exploration gives us seven elements that comprise the core themes of our book. We can summarize each of these themes with a driving question:

- Problem exploration: What problem should you solve?

- Solution: Is the solution fit for purpose?

- Customer: Who pays? For what? Why and how?

- Finance: How do you finance your solution?

- Policy: Is policy in your favor?

- Planet: If it works, does it matter?

- Scaling: How do you build it at scale?

Entrepreneurship Development Program

In person at MIT Sloan

Register Now

What type of ventures will benefit from this approach?

While we realize the title of our book implies a focus on new ventures, the real focus is on entrepreneurs, whether they are in startups or inside other, often larger existing organizations. There are all sorts of innovators who are addressing climate and energy challenges. Here are just a few of the types of ventures that we hope to support:

- Deep tech: Ventures commercializing complex technology based on novel scientific developments. Deep tech ventures often originate from laboratory research, and in the climate and energy space, they often need to be implemented at infrastructure scale to achieve their full potential impact.

- Hardware: Physical products, not necessarily based on laboratory research. These solutions are usually smaller than infrastructure scale and faster to build and deploy.

- Software: Digital solutions that accelerate emissions reduction, adaptation, or other climate- and energy-related objectives.

- Project development: Identifying, planning, and executing large-scale climate and energy projects to deploy existing technology at infrastructure scale.

- Business model innovation: Deploying existing technology with a novel business model that enables faster scaling. The other types of ventures can all use business model innovation, but it is worth calling it out specifically because it is a critical pathway for scaling climate and energy solutions.

“Disciplined Entrepreneurship for Climate and Energy Ventures” will be relevant for all these ventures, but we wrote it with deep tech in mind in particular. There are already many books about how to start software companies. There are fewer books about how to start hardware companies but still a lot. There are hardly any entrepreneurship books with a focus on deep tech. That is a critical gap in the entrepreneurship literature. We need deep tech to solve the climate and energy problems of the 21st century (and probably subsequent centuries, too).

Excerpted with permission from the publisher, Wiley, from “Disciplined Entrepreneurship for Climate and Energy Ventures: 24 Steps to Build Solutions for People and the Planet,” by Ben Soltoff, Bill Aulet, Tod Hynes, Francis O’Sullivan, and Libby Wayman. Copyright © 2026 by John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Ben Soltoff is an entrepreneur in residence and the ecosystem-builder in residence at the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship. Bill Aulet is a professor of the practice and the managing director at the Trust Center. Tod Hynes is a senior lecturer at MIT Sloan and a co-founder and instructor in the MIT Climate and Energy Ventures course. Francis O’Sullivan and Libby Wayman are senior lecturers at MIT Sloan and instructors in the MIT Climate and Energy Ventures course.