Behavioral Science

How cultural psychology influences mask-wearing

COVID-19 won’t be the last pandemic, but understanding cultural differences in mask-wearing could help us be more prepared for the next global crisis.

The most enduring symbol of the COVID-19 pandemic is also a case study in how culture shapes the way people respond to a crisis.

In new research from MIT Sloan assistant professor the culture and globalization expert found that people in more collectivistic cultures were more likely to wear masks than people in more individualistic cultures during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Our research suggests that culture fundamentally shapes how people respond to crises like the COVID-19 pandemic. Understanding cultural differences not only provides insight into the current pandemic, but also helps the world prepare for future crises,” write Lu and his co-authors Peter Jin and Alexander English in their paper “Collectivism Predicts Mask Use During COVID-19."

A collectivistic culture is one in which group needs and interests are prioritized over the individual. In the context of mask-wearing, people in collectivistic cultures might be more inclined to consider wearing a mask both a civic responsibility and a sign of solidarity that everyone is in this [the pandemic] together. In contrast, an individualistic culture is one in which individual goals and interests take priority over the group. People in these cultures might be more inclined to say that they are free to choose not to wear a mask, or in the case of some anti-mask protesters: “If I’m going to get COVID and die from it, then so be it.”

A number of factors contribute to the transmission of COVID-19, however, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advises wearing masks to slow and stop transmission of the virus.

The link between collectivism and mask usage

Based on a commonly used collectivism-individualism index in cultural psychology, some countries are more collectivistic, such as South Korea, the United Arab Emirates, and Vietnam. By contrast, other countries are more individualistic, such as the Netherlands, the U.S., and South Africa.

To test their hypothesis that people in more collectivistic cultures were more likely to wear masks, the researchers ran four large-scale studies.

Two of the studies examined between-country differences:

- One study used data from a YouGov and Institute of Global Health Innovation survey that asked: “How often have you worn a face mask outside your home (e.g., when on public transport, going to a supermarket?)” (0 = not at all, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = always) between April 1 and September 20, 2020. The dataset included about 367,000 people in 29 countries and territories. The gender breakdown was roughly 50-50 and the mean age of respondents was 43.

- Another study used data from a global survey conducted by Facebook and MIT between July 6 and September 23, 2020. The survey asked respondents whether they wore a face mask or covering to prevent COVID-19 infection in the past week (1 = yes, 0 = no). The respondents were at least 18 years old, about 45% female, and represented about 277,000 Facebook users across 67 countries and territories.

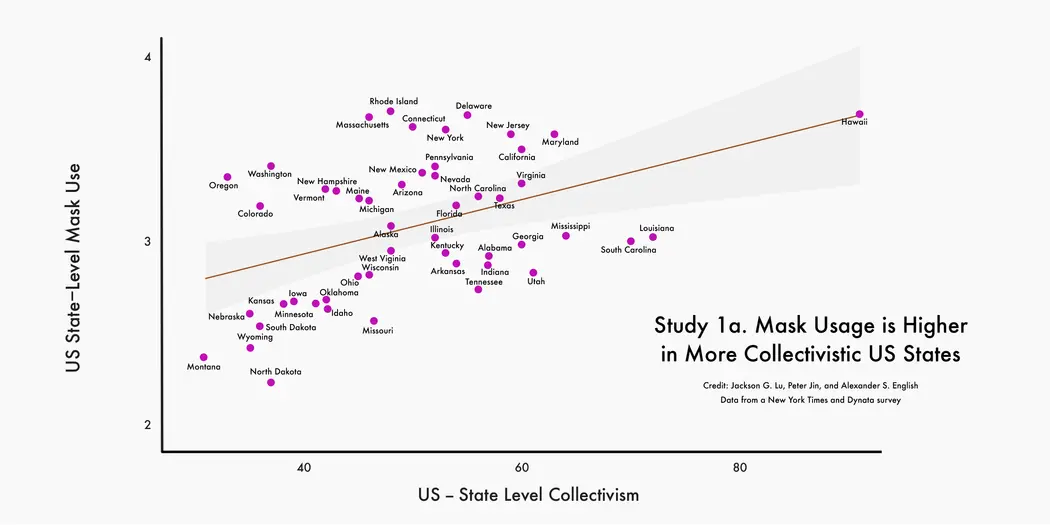

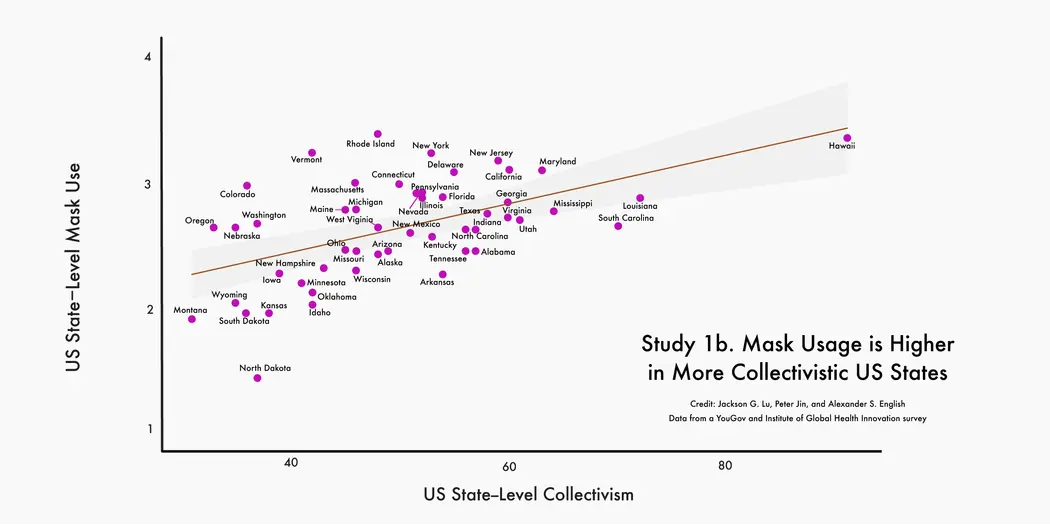

Notably, the link between collectivism and mask usage is not limited to between-country differences. The researchers found that even within the U.S., mask usage was higher in more collectivistic states such as California, Maryland, and Virginia, than in more individualistic states like Montana, Nebraska, and Oregon.

- A third study used data from a New York Times and Dynata survey that asked: “How often do you wear a mask in public when you expect to be within six feet of another person?” (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, 4 = always) between July 2-14, 2020. The dataset was made up of nearly 250,000 people across all 3,141 counties in the 50 U.S. states.

- Another study used data from the YouGov and Institute of Global Health Innovation survey. This dataset included 16,737 people across all 50 U.S. states — about 54% female and a mean age of 48.

Across all four studies, collectivism reliably predicted mask use, even after the researchers accounted for factors such as political affiliation, demographics, population density, socio-economic indicators, universal health coverage, government response stringency, time, and cultural tightness-looseness — “the degree to which social entities have many strongly enforced rules and little tolerance for deviance.”

“A key implication of our research is that, net of other factors, more collectivistic cultures are less vulnerable to global crises like the COVID-19 pandemic,” the researchers write. “To curb the pandemic, it is critical that people prioritize the collective welfare over personal convenience.”

Global perspectives, and recommendations

MIT Sloan Deputy Deanhas lived and worked on and off in Tokyo, Japan since the mid-1970s. The country sits in the middle of the collectivism-individualism index used by the researchers.

Cusumano was in the capital city when COVID arrived in early 2020.

“If you went anywhere in Tokyo or Yokohama then, you saw most people with medical facemasks,” Cusumano said. “This was not because of the virus, but because it is common practice in Japanese cities to wear masks in the wintertime to prevent catching or spreading the flu and colds.”

a professor of global economics and management at MIT Sloan, said Lu’s research exposes a fallacy about strong, authoritarian governments being best positioned to manage COVID-19.

“Many point to China as an illustration — even on the surface this argument is problematic,” Huang said. “Democratic Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have been equally successful, if not more successful, than China has in containing the infection and mortality rates. Culture, not political system, is the common denominator. Professor Lu’s research validates this perspective and does so using data and careful empirics.”

Huang said he was also struck by the mask-wearing patterns and the collectivistic and individualistic divide within the United States.

“This paper has a number of recommendations that I think public health officials ought to take very seriously,” Huang added.

Those recommendations, based on behavioral science, include:

- Featuring the voices of “convert communicators,” who once believed mask-wearing was unnecessary, and can tell nonpolitical stories explaining why they changed their minds.

- Emphasizing that wearing masks is a choice, not a mandate.

- Featuring images of many individuals wearing masks.

- Encouraging businesses to normalize mask-wearing by integrating it into existing requirements: “No shoes, no shirt, no mask, no service.”

- Communicating the benefit of mask use to the community, not just the individual.