Future of Work

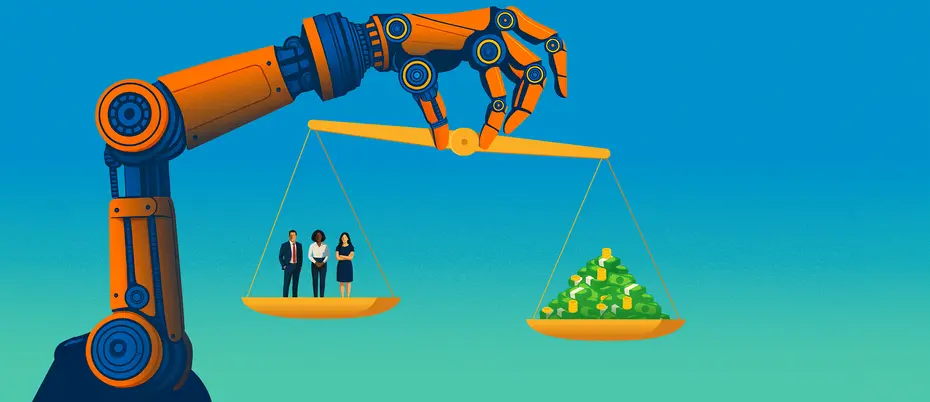

A new look at how automation changes the value of labor

Automation replaces experts in some occupations while augmenting expertise in others, according to a new MIT study.

As automation accelerates and large language models continue to improve, the dominant narrative has been about displacement: Technology takes over human tasks, roles are eroded, and wages suffer.

But new research from MIT’s David Autor and Neil Thompson challenges the view that automation is always bad for workers. In a sweeping study of U.S. occupations, the authors examined a long-standing economic puzzle: why some jobs that appear highly exposed to automation have not seen the wage collapse predicted by earlier models.

In fact, their research shows that in some cases, pay has gone up. For instance, bookkeepers and accounting clerks saw computers take over many of their tasks between 1980 and 2018. Yet even as total employment in these roles fell by a third, their real hourly wages rose by nearly 40%.

The reason: If automation removes the simpler parts of a job, the work that remains often demands more expertise — which can make that work more valued and better paid because fewer people are qualified to do it.

But when automation targets the specialized tasks instead, the job may become easier for others to enter, increasing competition and putting downward pressure on wages.

Like bookkeepers, inventory clerks were also highly exposed to computerization. But as automation targeted their most expert tasks, and employment in the role more than doubled, their real wages fell by 13%.

“Jobs can either become more or less numerous, depending on what types of automation happen to the job,” said Thompson, a principal research scientist at the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy. “If the thing that gets automated is the easiest task, that leads to a narrowing of the pool of people that do it. But they are paid more.”

The research shows that when business leaders think about how AI will change work, they should think beyond who is exposed to automation and also consider how it changes what people need to know to do a job.

How automation alters roles and wages

In seeking to understand why and how the nature of work has changed over four decades, the authors developed an “expertise framework” to measure how much expertise different tasks require. Rather than relying on job titles or opinion surveys, they analyzed the language used to describe the work itself.

Task descriptions that include specialized terms — like those for operating diagnostic imaging equipment or forecasting economic trends — tend to require more expertise. Simpler tasks, such as boxing lightweight items or greeting customers, do not.

Using this language-based approach, the authors tracked how the average expertise level of more than 300 occupations changed between 1980 and 2018.

They found that when simpler tasks disappeared, jobs became more specialized — and often better paid — even as employment declined. But when automation removed the more expert tasks, wages tended to fall as more people moved into the role.

“Taxi drivers, for example, once relied on deep knowledge of local streets, which was a real differentiator,” Thompson said. “But with the arrival of GPS, that expertise was automated. The result is a more commoditized taxi service: lower wages, but many more drivers.”

This shift can create opportunities as well. “There will be new professions that open up to people,” Thompson said, “because automation removes the hardest parts that used to be out of reach.”

AI Executive Academy

In person at MIT Sloan

Register Now

Practical implications for employers

The effects of automation require different management responses, depending on what kind of work is being automated, Thompson said.

- If automation drives wages up but shrinks the number of people needed in a role, companies can often adapt gradually — for instance, by not replacing workers when they leave. “That’s something you can manage through attrition,” Thompson said.

- If wages go down and the job becomes less specialized, the adjustment is harder. Lower pay can hurt worker morale and make recruitment and retention more difficult.

“Depending on which tasks are automated, you’ll see different effects in different parts of your workforce,” Thompson said. “You want to think about that ahead of time because it calls for different responses from the company.”

Related Articles

In some cases, leaders could design more specialized, high-value roles that retain expert tasks. In others, automation could be used to make certain jobs easier to access and expand the talent pool. Either way, companies have more control than they might assume.

That variability is central to the study’s argument. The authors do not suggest that automation is always good or bad for workers — only that its impact is more nuanced than many people assume.

The research indicates that automation doesn’t just reduce the need for human work. Sometimes it concentrates it around the tasks that are hardest to replace, and when it does, the value of that remaining human expertise can rise — and with it, wages, too.

This article is based on work by Neil Thompson and David Autor. Thompson is a principal research scientist at MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and the MIT Sloan Initiative on the Digital Economy, and director of the MIT FutureTech lab. He studies technological innovation and firm strategy. Autor is a professor of economics at MIT and co-director of the MIT Stone Center on Inequality and Shaping the Future of Work. His research explores labor-market consequences of technological change.